Nations are not built by those who sit down and ask for doles or alms, but by the daring and the bold. They are not built by the timid, but by the dauntless and adventurous.

Maryborough was truly an essential industrial city in Queensland’s early history. It served as a pivotal distribution centre that supported three major industries: agriculture, manufacturing, and timber. Its advantage came from having a port along a river highway, well before roads, cars and trucks came into vogue.

One example of a resourceful business was the establishment of a heavy engineering and manufacturing company that began close to the goldfields at Ballarat in 1864.

The founding principal was John Walker, who, along with James Wood and Thomas Braddock, established a firm that grew into one of the largest iron foundries in the Commonwealth. They recognised the significant opportunities in supplying Queensland’s expanding engineering needs, particularly in the booming mining and sugar industries following the discovery of gold at Gympie. In 1868, they established a new branch of the parent company in Maryborough and began operations, setting up workshops under the business name of Union Foundry.

By 1869, 28 sugar mills were processing sugar cane across 5,000 acres in Queensland. This figure surged to 157 mills by 1884, primarily due to the influx of inexpensive indentured labour from the Pacific Islands.

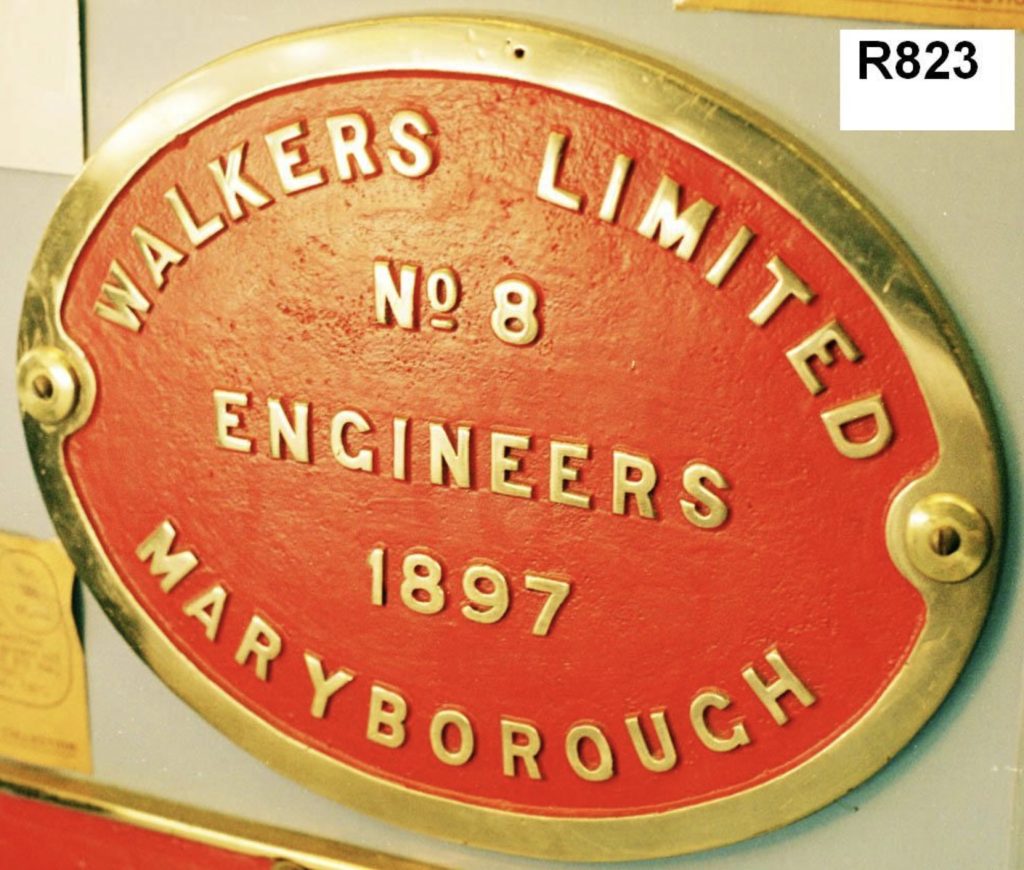

In 1872, William Harrington became the fourth partner in the company, eventually rising to the positions of Managing Director and Chairman after the business was floated as a public company under John Walker & Co. Limited. In 1888, a new company was registered to facilitate the division of the original £100 shares into £5 shares, and the name Walkers Limited was selected.

In 1879, half of the original business in Ballarat was sold to allow the company to keep expanding the Maryborough facility, which led to the four partners moving to Maryborough. The shipyard workshops for shape lofting and preparing wrought iron plates and sections for riveted construction were built facing Kent Street. A tramway connected the foundry on higher ground, and an inclined slipway for ship construction was also constructed.

Walker retired in 1881 and was succeeded by the experienced engineer Alfred Goldsmith. Goldsmith took charge of the shipbuilding department, which was established to construct river dredges, hopper barges, and other vessels.

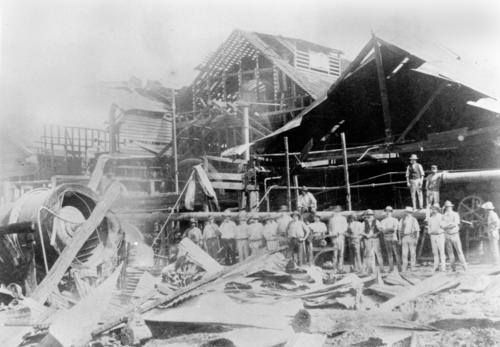

The 1893 flood was highly devastating to Maryborough’s industrial businesses located along the river. It obliterated the Hyne and Son sawmill, which was positioned between Walker’s building and the river, prompting a relocation to higher ground further upstream. Walker’s shipyard and buildings were also destroyed. A new flood-resistant factory was built, which successfully withstood future major floods.

A key factor in Walkers’ long-term success was its diversified business model. While many engineering firms were vulnerable to downturns in a single industry, Walkers operated across multiple sectors—including sugar milling, railway engineering, shipbuilding, and mining equipment manufacturing. This variety provided a buffer against economic fluctuations; when demand for railway locomotives slowed, contracts for shipbuilding or sugar machinery often kept production lines running. Similarly, during economic downturns that impacted private industry, government contracts for railway and infrastructure projects helped sustain operations. This adaptability ensured that Walkers remained a resilient and dominant force in Australian heavy engineering for over a century.

Powering the gold and mining boom

The discovery of gold at Nash’s Gully in Gympie in 1867 sparked a mining boom in Queensland and helped save the struggling colony from financial ruin. While alluvial gold was quickly depleted in Gympie, mining activity spread throughout the state, uncovering rich deposits of coal, copper, silver, lead, zinc, tin, wolfram, and molybdenite. The mining industry became a cornerstone of Queensland’s economy, driving infrastructure development and generating sustained demand for heavy engineering.

In the same year Walkers opened their foundry in Maryborough, the Ravenswood goldfield was discovered, followed by Charters Towers in 1871 and the Palmer River alluvial field in 1873. The establishment of Mount Morgan in 1882—the state’s largest and most famous gold mine—marked the beginning of large-scale mining operations in Queensland. Walkers quickly became a key supplier to these and many other mining ventures as they knew the mines would require essential equipment such as steam engines and machinery to enable them to boost production and enhance efficiency.

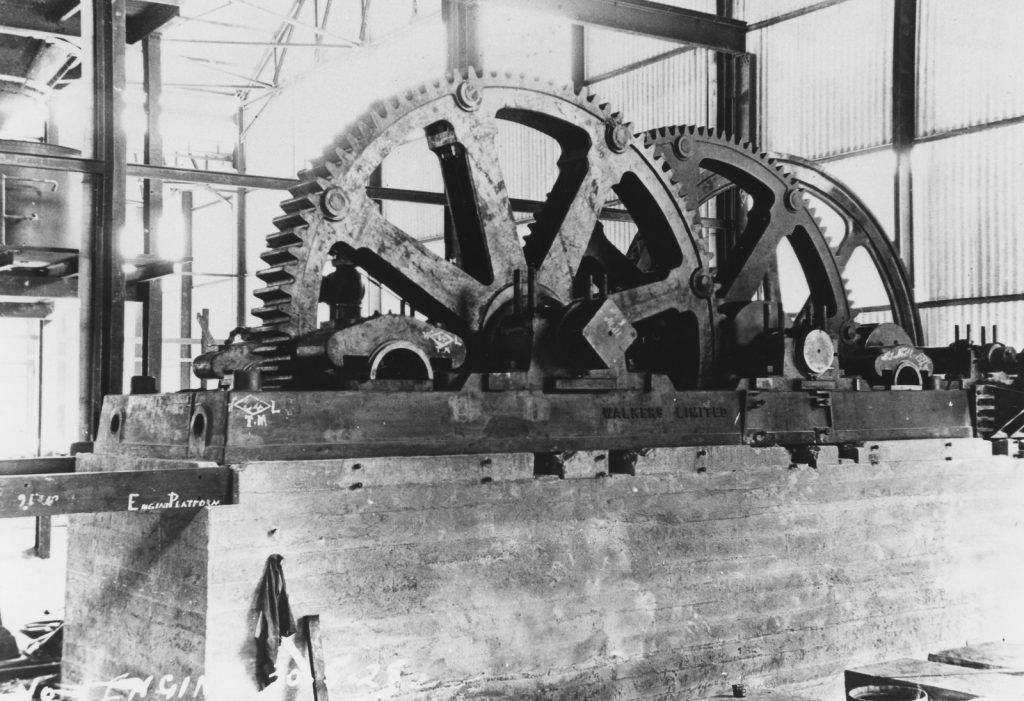

Initially, Walkers concentrated on manufacturing heavy stamping and crushing machinery crucial for breaking down gold-bearing quartz. They provided stamp batteries, belted high-speed Krom Rolls, Wheeler pans, and Huntingdon mills for ore grinding—each representing an innovation that enhanced gold recovery rates. Their winding machines, used for hoisting ore and miners from deep shafts, earned such a strong reputation that they were distributed to mines across all Australian states.

Walkers also played a critical role in smelting and processing technology advancement. Their Cornish and Lancashire boilers were regarded as state-of-the-art, providing the steam power needed to drive mining machinery. When the cyanidation process was introduced in 1890, revolutionising gold extraction, Walkers was at the forefront, supplying some of the largest mines with cyanide processing plants. Their expertise extended to smelting operations, designing and constructing smelters, mine chimneys, and other essential infrastructure, ensuring Queensland’s mining sector remained competitive with international goldfields.

As Queensland’s mining industry evolved beyond gold, Walkers continued to innovate by supplying specialised equipment for coal and base metal mines. Their ability to adapt to new mining technologies and techniques ensured they remained a dominant force in the engineering sector, supporting mining operations in Queensland, throughout Australia, and overseas.

Mechanising Queensland’s sweet success

As Queensland’s sugar industry grew, Walkers became a vital partner in its development. The company initially supplied much of the machinery for the early sugar mills. It evolved to produce modern crushing and evaporative plants that greatly enhanced sugar yield per ton of cane.

From 1870, with the industry’s rapid growth, Walkers moved from supplying individual components to becoming the preferred manufacturer for complete mill systems. Their expertise extended beyond crushing equipment and included boilers, vacuum pans, and centrifuges—essential components in the sugar refining process. The company also played a significant role in developing cane railway systems, designing and creating small yet robust locomotives to transport freshly harvested cane from the fields to the mills.

To meet the growing demand, Walkers brought in skilled tradesmen from England and trained a local workforce in the specialist engineering skills needed to manufacture and maintain complex sugar-processing machinery.

Recognising the need for a more efficient milling system, the Queensland Government introduced the concept of central mills—larger, more effective operations intended to service multiple growers. Walkers played a key role in this transition by constructing six central mills located at Marian, Proserpine, Plane Creek, Bauple, Gin Gin, Isis, and Maryborough. They also provided machinery to numerous other mills, ensuring the ongoing modernisation and success of the sugar industry.

By the early 20th century, Walkers had established its reputation as the leading engineering firm for sugar production. They pioneered innovations that allowed Queensland to become a world leader in sugar exports. Their influence stretched beyond Queensland, with Walkers-built machinery present in sugar mills across Australia and the Asia-Pacific region.

Driving progress across Australia

Queensland’s first locomotive was built by Walkers as early as 1873. Recognising the inefficiency of bullock teams on sandy terrain, Scottish immigrant and sawmiller William Pettigrew, along with his business partner William Sim, pioneered tramways for log transport. They constructed Queensland’s first privately owned railway—a 9-mile wooden tramway—on the Cooloola sands, connecting their timber operations to the water’s edge at Tin Can Bay. They commissioned Walkers to build a locomotive to power the tramway, initially called Puffing Billy but soon renamed Mary Ann after Pettigrew’s and Sim’s daughters.

By the late 19th century, Walkers had expanded beyond its original sugar machinery and shipbuilding operations, shifting its focus to railway engineering. The next locomotive was constructed in 1896, and by 1898, the company secured its first contract with the Queensland Government to supply railway locomotives. This marked the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship with the railway sector, leading to ongoing contracts for locomotives from the Victorian, South Australian, and Commonwealth governments. Between 1909 and 1925, Walkers built an impressive total of 310 locomotives, with production peaking at one locomotive per week.

During the Great Depression, economic hardship significantly reduced railway demand, resulting in Walkers’ workforce shrinking to just 64 employees under the management of Herbert Goldsmith, son of Alfred Goldsmith. In a bid to sustain the company, Goldsmith successfully negotiated a contract to manufacture diesel engines under license from a British firm, ensuring Walkers remained a key player in heavy engineering.

With the outbreak of the Pacific War, Queensland became a vital military hub, putting immense pressure on the railway network as military transport demands soared. Despite significant material shortages, Walkers successfully increased production, constructing locomotives to bolster the war effort. The company also played a key role in supplying thousands of cast steel wheel centres for rolling stock, ensuring that the rail system could meet its massive logistical needs.

Beyond locomotives, Walkers made significant contributions to railway infrastructure. They provided the steel for key railway bridges along the North Coast and Atherton lines and manufactured essential structural components for major infrastructure projects in Queensland. Their foundry produced the Victoria Bridge piers, the Story Bridge’s base castings, and numerous Queensland Railways cranes used in track laying. Many cast iron water tanks that supported steam locomotives across the state also originated from Walkers’ workshops, further solidifying their role as an engineering powerhouse.

By the mid-20th century, Walkers had established itself as one of Australia’s leading locomotive manufacturers. The company’s expansion is evident in its production of locomotives. They built their 100th railway locomotive in 1909, their 200th by 1914, their 500th after WWII, and their 681st by 2017.

Walkers adapted to new technologies and ensured the ongoing development of Queensland’s railway network. They made steel castings even before BHP entered the steel business, built the first big 200 horsepower engine in 1932, which for years was the largest diesel engine built in Australia, and pioneered the construction of diesel-hydraulic locomotives.

From hopper barges to warships

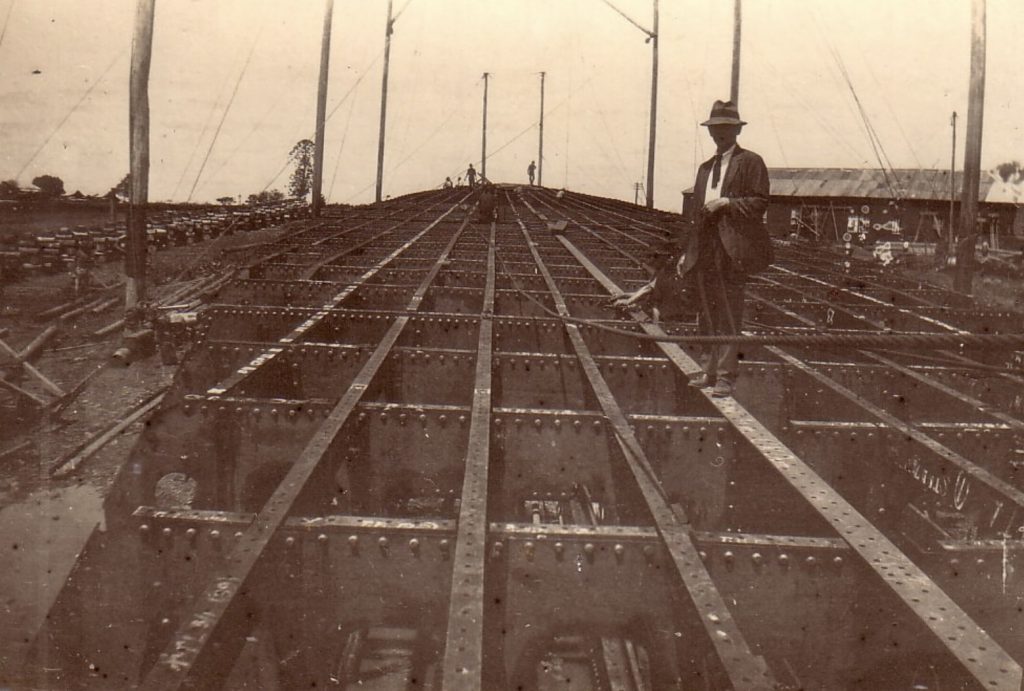

Walkers’ shipbuilding operations commenced in 1877 on a ten-acre site along the Mary River, between Kent and Guava Streets, in response to a Queensland Government request for three screw-driven steam hopper barges for the Brisbane River. Constructed with imported Lomore wrought iron plates and sections, each vessel measured 135 feet in length and had a spoil capacity of 350 tons. Completed in 1879, the vessels were named Schnapper, Dugong, and Nautilus.

From the 1880s, shipping was extremely important to Queensland, and Walkers played a crucial role in building much-needed seafaring vessels.

Next, Walkers constructed two self-propelled steam bucket dredges, Surian and Maryborough, for the Queensland Government. Maryborough operated for 60 years, primarily dredging around its namesake port. In the years leading up to 1898, Walkers built 13 vessels, firmly establishing themselves as a prominent shipbuilder.

As shipbuilding declined during WWI and the 1920s-30s, Walkers shifted their focus to other engineering sectors. However, between 1918 and 1928, three vessels were constructed as part of the Commonwealth Government’s initiative to develop its own shipping line.

This initiative arose from two main factors. First, the British merchant fleet had lost nearly 2,500 vessels during WWI, leading to a shipping shortage and soaring freight costs. Second, establishing BHP’s Newcastle steelworks provided Australia with a domestic steel supply, lessening reliance on imported materials.

When confronted with industrial unrest at the preferred Williamstown shipyard in Victoria, Prime Minister Billy Hughes turned to alternative shipbuilders. The Commonwealth commissioned 21 cargo ships—referred to as Billy Hughes ships—from various shipyards. Walkers received orders for four E-Class cargo vessels, necessitating significant upgrades to their slipway, including constructing two new building berths on timber pile foundations.

In 1921, two ships, Echuca and Echunga, were launched, each with a deadweight capacity of 6,000 tons. However, the other two orders were cancelled, leading to the cessation of Walkers’ shipbuilding activities once more. The last major construction project from this period was Platypus II, a twin-screw steam-driven bucket hopper dredge built for the Queensland Department of Harbours and Marine in 1925.

With the outbreak of WWII in 1939, Australia faced a severe shortage of naval vessels. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) initiated an ambitious fleet expansion, commissioning a class of Local Defence Vessels, later known as corvettes, for minesweeping and anti-submarine tasks. Designed by the British Admiralty and funded by the Royal Navy, 60 corvettes were constructed in Australian shipyards between 1940 and 1943. World War II provided opportunities for Walkers that they took advantage of.

They secured contracts for seven corvettes, dramatically reviving its shipyard and boosting its workforce to over 1,000. The first vessel, HMAS Maryborough, was commissioned in June 1941. Despite being designed for coastal operations, she and her sister ships—Toowoomba, Rockhampton, Cairns, Tamworth, Bowen, and Gladstone—served extensively in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, escorting convoys and clearing mines.

As the war progressed, the RAN needed larger, more capable vessels. Walkers received contracts to build three River-class frigates—Burdekin, Diamantina, and Shoalhaven. At 300 feet long, these ships boasted advanced sonar for submarine detection, anti-aircraft weaponry, and long-range escort capabilities. A fourth frigate order was cancelled at the war’s end.

As the conflict drew to a close, Walkers constructed three 93-foot diesel tugs—Boray, Boambilly, and Burrowaree—which were handed over to the Maritime Services Board of New South Wales upon delivery.

In addition to shipbuilding, Walkers played a vital role in wartime production. They manufactured 40 triple-expansion steam engines (875-2,750 horsepower), with 20 of these installed in ships built in Maryborough. They also produced propeller shafts and Mitchell thrust blocks for ship propulsion, 114 Admiralty-type steam-driven pumps, 1,000 watertight steel doors, 79 cargo steam winches, and thousands of bronze valves and fittings.

At its wartime peak, Walkers employed 1,200 workers on demanding 56-hour work weeks.

In 1963, Walkers initiated a significant shipyard modernisation, investing $670,000 to enhance facilities for welded ship construction. These improvements allowed for the construction of vessels up to 350 feet long, 55 feet wide, and with a launching weight of 2,500 tons, whilst maintaining the flexibility to assemble smaller crafts. The upgrades aimed to boost efficiency and keep costs competitive.

One of Walkers’ last major naval projects was the construction of Attack-class patrol boats in 1967-68. These were built for the RAN at two Queensland shipyards—Evans Deakin in Brisbane and Walkers in Maryborough.

The 1974 floods in late January effectively ended the shipbuilding business. During the second half of 1973, Walkers announced a loss of $1.056 million wholly in its shipyard after a major industrial dispute with the union on over-award variations, which the company were liable for if there were any delays in meeting contract delivery times. On 2 February, they announced the shipyard’s closure upon completing the second Smit Lloyd vessel being built. At the time, there were 300 employees in the shipyard.

Walkers’ shipbuilding legacy spanned nearly a century, from pioneering Queensland’s early steam vessels to supplying naval ships critical to Australia’s defence during World War II. Almost 70 ships were built between 1877 and 1974.

While the company later shifted its focus, its contributions to Australia’s maritime industry remain a testament to its engineering ingenuity and adaptability. This was reflected in its performance—between 1877 and 1974, Walkers built 68 ships, from tugs and dredges to patrol boats for the Navy.

Walkers’ history is deeply intertwined with Maryborough’s industrial powerhouse development, which peaked in the 1940s and 50s. There were two large sawmills milling hardwoods from Fraser Island, and many apprentices trained at Walkers, the sawmills and the sugar mill.

For a city of 20-22,000 people, 1,600 worked at Walkers, making it the city’s largest employer for over a century. Walkers provided livelihoods for thousands of skilled tradesmen, engineers, and labourers. It shaped Maryborough’s identity as a centre of heavy industry, bringing economic prosperity and fostering generations of expertise in metalworking, shipbuilding, and locomotive manufacturing.

As the demand for Australian-built vessels diminished, Walkers’ shipbuilding operations slowly declined in the late 20th century. Throughout the 1970s, increasing labour costs, competition from overseas shipyards, and changes in government defence procurement strategies resulted in a notable decline in domestic ship construction. Walkers constructed its last major naval vessels in the 1970s, marking the conclusion of an era that had lasted over a century.

Despite this, the company stayed a leader in engineering and heavy manufacturing. By the late 20th century, Walkers shifted its focus towards producing locomotives and industrial machinery, maintaining its reputation for precision engineering.

In the 1980, Walkers was acquired by Evans Deakin Industries, another established engineering firm based in Queensland. This merger further strengthened the heavy industry sector in Australia, with Evans Deakin joining Downer EDI in 2001. The Maryborough facility continued to function under Downer’s rail division, which specialises in the manufacturing and maintenance of rolling stock. In 1994, EDI, in a consortium with two Japanese companies, won the contract to build two tilt-trains, the first of their type in Australia, to run between Brisbane and Rockhampton.

Although the Walkers name has faded from the shipbuilding scene, its legacy endures in Australia’s maritime and industrial history. The company played a vital role in Queensland’s early development, made significant contributions to wartime shipbuilding efforts, and helped shape Australia’s engineering capabilities. The Maryborough site continues to thrive in locomotive construction, upholding Walkers’ tradition of industrial innovation well into the 21st century.

In the history of Queensland manufacturing enterprises, Walkers must never be forgotten.

Christopher Hughes

Postscript

One can’t write about Walkers without mentioning the 5 o’clock whistle, which saw workers leaving the site in droves, bound for home on their bikes. This followed the 4 o’clock whistle at the railway yards, where those workers had to clear the city centre before the Walker deluge.

We need such businesses for Australia’s development, regional development and having sound capacity to build boats and other equipment in war time. They are a coming.

Congratulations Robert on keeping up the flow of very interesting histories.

In 2016, I visited the riverside museum in Maryborough and was amazed to learn that seven of the 60 wartime Bathurst class corvettes had been built on the river by Walkers. As a young midshipman in 1970, I had been on training cruises on one of those 60, HMAS Kiama, which was transferred to the RNZN in the early 1950s and commissioned as HMNZS Kiama. It was scrapped in the mid-1970s.

The Bathurst class ships were built in yards all over eastern Australia. HMAS Kiama was Queensland built, not by Walkers but by Evans Deakin Co at Kangaroo Point on the Brisbane River. Their greatest legacy now is as the builders, along with Hornibrook, of the Story Bridge. Like Walkers, Evans Deakin is long gone through mergers and acquisitions, but an echo remains in the name of Downer EDI.

Thanks, Robert, for your potted history of Walkers. Alongside Evans Deakin, they were arguably Queensland’s greatest engineering companies, making their inestimable contribution to the state’s development and the nation’s war effort during WW2.

Walkers’ ghosts now haunt Downers EDI.

As a later arrival to the Fraser Coast much of the industrial and commercial might of Maryborough had faded by the time I arrived but I’ve always been keen to learn as much as I could about that time.

This blog of Robert’s has broadened my view greatly. Many of my informal perceptions of Walkers were gained as a member of Walkers Engineering Works Band. Whilst the band was not formally a “works band”, as was often the case in the UK, several members still worked at Walkers in my time, and I vividly remember being entertained in rehearsal breaks by those members spinning yarns about life in the Works and the many characters who worked there.

The band, originally formed as the Junior Naval Band, became the Maryborough Federal Band Qld in 1919 and was named after the local brewery. When the brewery closed, I was told the Federal Band needed a new name. With so many players working in Walkers, the decision was made to name the band after the iconic Maryborough business.

When Walkers became Downer EDI in 2005, the band had to change its name again and became Maryborough Brass.

Thanks Robert, I enjoyed the read.

Walkers was still pretty active in the early 80s when I was living in Maryborough.

Keep up the good work!!