Point Nepean, located at the tip of Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, is a site of remarkable historical significance. It houses Australia’s second-oldest surviving barracks-style quarantine buildings and fortifications that once protected the colony’s coastline. As the primary quarantine station in Victoria until 1979, Point Nepean played a pivotal role in safeguarding public health. Its later transformation into a military stronghold further cemented its place in history. Today, this unique site is preserved within the Point Nepean National Park, offering visitors a glimpse into its multifaceted past.

Origin of quarantine measures

The need for quarantine in Australia became evident as early as 1790 when a smallpox outbreak devastated Indigenous populations in Sydney.

The British passed the Quarantine Act in 1825 to prevent the spread of diseases like cholera and yellow fever, shaping Australian quarantine policies. They involved the detention of passengers for up to 30 days or longer and the opening and airing of the ship’s cargo for up to 40 days.

By the 1840s, Victoria’s Port Phillip saw increasing immigration, and the arrival of diseases such as typhoid alarmed authorities. They were anxious to introduce better measures to protect the health of its residents. While the number of immigrant ships was relatively low, authorities accommodated new entries in tents on shore when they arrived and kept the ill on board the quarantined ship.

The overcrowding and unsanitary conditions on ships certainly didn’t help. There were reports in the newspapers that bodies from quarantined ships were thrown, unweighted, overboard, and fishermen had even caught one in a net.

The Gold Rush of the early 1850s, which brought a net immigration of 70,000 people, underscored the necessity for a dedicated quarantine station. Several sites were investigated and trailed around Melbourne, but the authority’s hands were full as more and more ships arrived. In response, they hired empty vessels for quarantine purposes, which proved unsatisfactory. Crowding people into small spaces only increased the risk of disease spread.

After the Port Health Officer’s report in 1852, authorities selected Point Nepean for its isolated location and suitable anchorage.

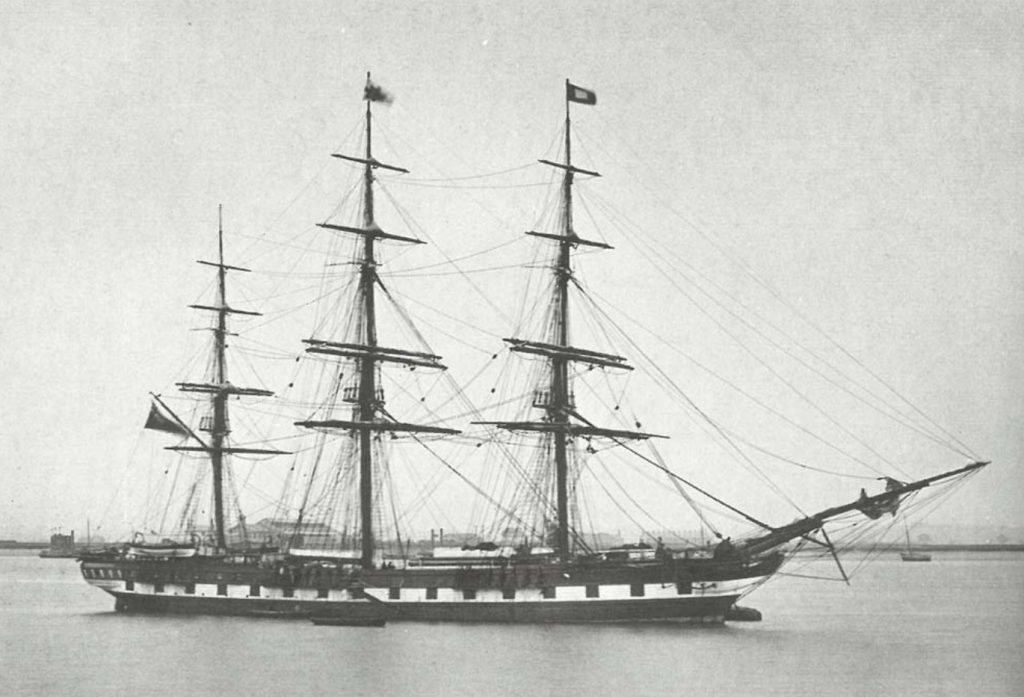

However, the site faced an immediate test when the immigrant ship Ticonderoga, carrying 800 souls, arrived with scarlatina and typhus, necessitating a hasty setup of quarantine facilities. Makeshift huts and tents initially served as accommodations, and conditions were dire.

Over 100 passengers died during its journey from Liverpool. The problem was so acute that Daniel Sullivan and his family, settlers adjoining the station, were turned out of their several buildings they occupied under licence from the Crown, including the lime burner that operated a lime kiln. The government immediately purchased these buildings for a hastily established sanatory station.

Life in isolation: early challenges and improvements

The fledgling station struggled to cope with the demand in its early years. Facilities were sparse and primitive, making it difficult for immigrants and those in charge. Two rough huts and makeshift tents composed of sails and spars of a ship were not enough. Those well enough chose to shelter among the trees with blankets stretched over the branches. It is not surprising that many of the newcomers absconded at the first opportunity.

By 1853, timber arrived to construct the permanent buildings, including hospitals and administrative centres. The station could house patients the following year instead of on the hospital ships offshore. The site’s formal gazettal as a Quarantine Station marked a turning point.

The new resident Medical Officer, Dr Reed, reported in the 1857 Annual Report:

Our accommodations on the sanitary station, either for the purposes of ablution, or for treating disease, or for providing for healthy immigrants, have been very meagre.

However, he reported that they had “extinguished” any disease on a detained ship, which was remarkable considering the staff consisted only of himself, a storekeeper, two labourers and a nurse. By the end of that year, workers had completed the construction of several buildings using local sandstone, including four hospitals, a boiler house, washrooms and an administrative centre. Police supervision enforced isolation during quarantine.

Each hospital had four large dormitory style rooms and from the 1870s were used by steerage passengers, or “lower class” immigrants. To the rear of the hospitals was the kitchen where the passengers prepared their own meals.

Quarantine measures were strict. Medical staff examined and vaccinated immigrants, provided them with hot showers, and fumigated their belongings with formaldehyde gas in a disinfecting oven and bedding via a steam saturation method within a sealed chamber.

Despite the challenges, many arrivals found the station’s clean air and fresh food a welcome change.

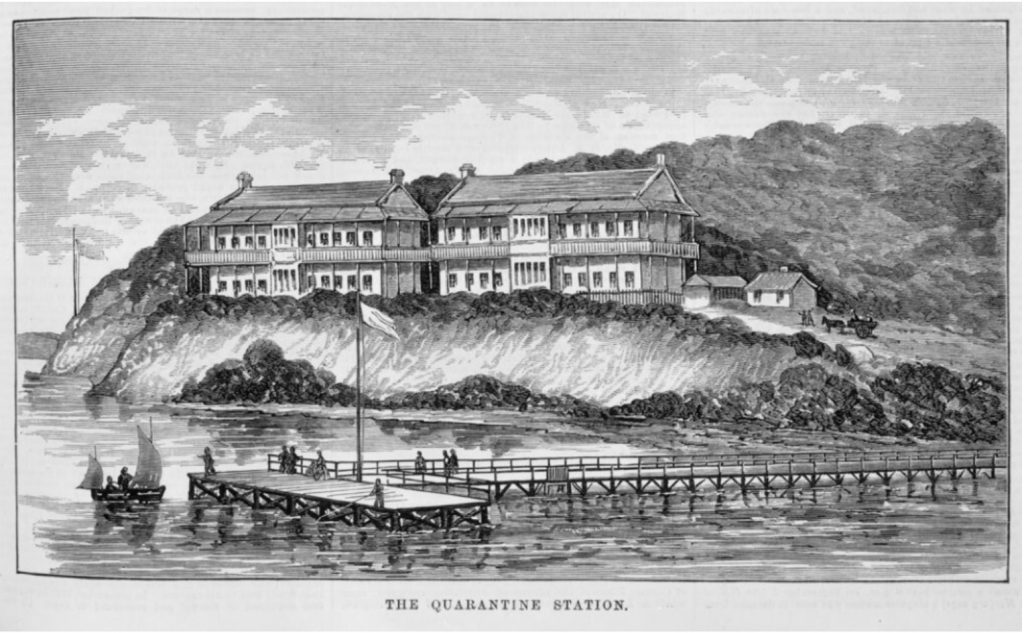

Gradually, conditions improved over time. By the 1880s, there were four large wards in each of the five hospitals or reception houses, three detached cookhouses, a stone bath and a washhouse. In total, there were 900 beds available.

The large administration building was built with a nice looking facade and was an impressive addition to the station. One of the last buildings added to the complex was the superintendent’s house. It was a smart residence on a hill overlooking the bay.

The first school in the area was also on the station grounds, but its operation was unsatisfactory. The station staff’s children and their teacher stayed inside, while nearby Portsea children sat on a bench outside the fence and received lessons through the barrier.

The role of livestock and leprosy quarantine

Point Nepean also played a critical role in safeguarding Australia’s agriculture. A jetty built in 1879 near Observatory Point facilitated the quarantine of livestock, with stables and holding yards constructed nearby. The station’s responsibilities extended to housing leprosy patients in isolated huts near Fort Nepean, further showcasing its diverse functions.

Epidemics and immigration: the station’s final years

In 1910, the Commonwealth took control of quarantine throughout Australia and changed its name to Portsea Quarantine Station. This distinguished it from other quarantine stations in different states.

It was during this time that the station was used for other purposes such as a summer school by the Victorian Department of Education.

The station experienced its busiest period during the 1918-19 Spanish Flu epidemic when staff quarantined 11,800 returning World War I soldiers. While the most common reason for quarantine was influenza, there were also cases of smallpox. Twelve timber “influenza huts” were built to accommodate the influx and treat affected soldiers.

The expense of maintaining such a large facility, some distance from Melbourne, was frequently cited as a reason to close the station. Proposals were constantly put forward to quarantine sick arrivals on ships in the bay, a cheaper but less healthy alternative. Compounding the issue, was that the station frequently sat empty after long stretches when ships arriving in Melbourne recorded no diseases.

Later, post-World War II immigration brought thousands of European refugees, who often viewed the towering chimney and disinfecting facilities as their first impression of Australia.

By 1966, ship quarantining ceased mainly due to the growth of international travel by air, and in 1980, the station closed following the World Health Organization’s declaration of smallpox eradication.

Even after its closure, Point Nepean’s role in providing refuge persisted. In 1999, the station temporarily housed nearly 400 Kosovo refugees, a poignant chapter in its history.

For thousands of immigrants, the station was their first life experience in Victoria. It proved to be a successful venture as the state, up to 2020, has been essentially free of severe epidemics serious enough to threaten either humans or animals.

From quarantine to fefence: fortifying Point Nepean

Point Nepean’s strategic location also made it a linchpin in Victoria’s coastal defences.

During the late 19th century, the government decided that Victoria’s fertile goldfields needed protection, particularly after several war scares in Europe. They prepared a defence plan for Melbourne. Due to its strategic position at the very end of the peninsula overlooking the entrance to Port Phillip Bay, Point Nepean became a vital defence post. The military constructed numerous fortifications, making Melbourne one of Australia’s most heavily defended sites and an excellent example of a significant fort complex. They included tunnels, forts and gun emplacements. They aimed to ensure that defenders fired on enemy ships attempting to enter the bay.

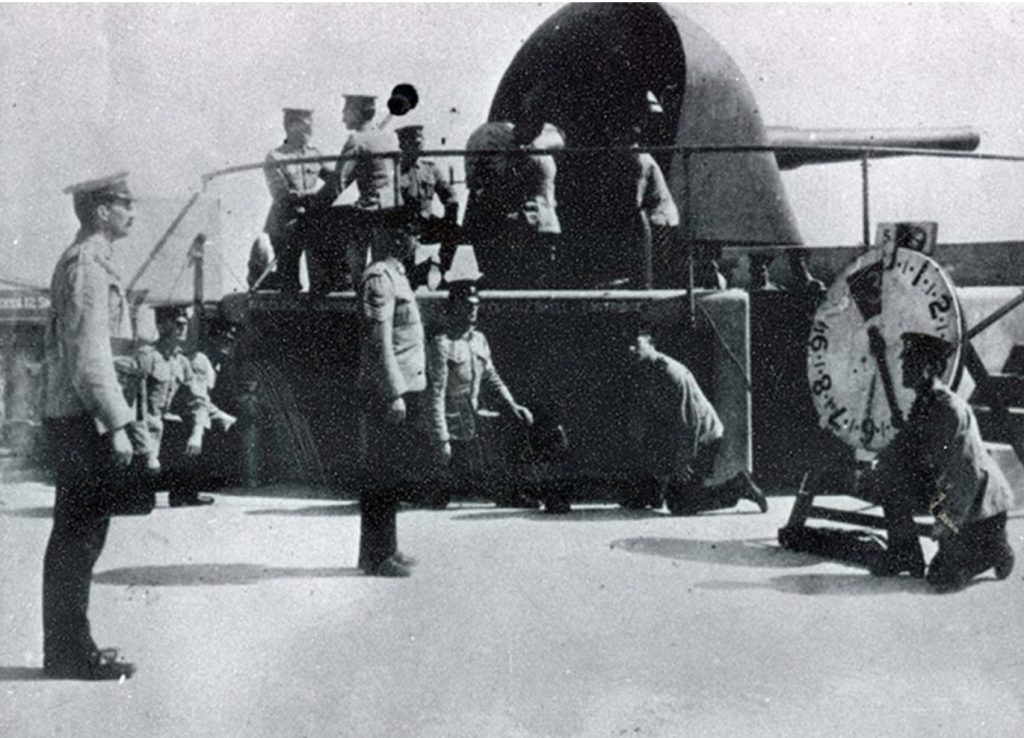

Fortifications began in 1878 at Fort Nepean at the headland’s tip, with initial armaments comprising 80-pounder muzzle-loading guns in u-shaped emplacements joined by an underground magazine and tunnel complex. Breech-loading guns were installed at Eagles Nest in 1889 and Fort Pearce in 1911.

In 1911, the Army replaced armaments with longer-range six-inch Mark VII guns. They remained in service until 1945 in response to potential air attacks, when the Army removed them after the forts were declared obsolete and decommissioned.

Point Nepean witnessed key wartime events. The first occurred just after the formal declaration of World War I on 5 August 1914. German steamer the Pfalz attempted to flee Melbourne hastily, and as it neared Port Phillips Heads, the war’s first shot was fired across the vessel’s bow, convincing the ship’s captain to stop. Authorities interned the ship and detained the first prisoners of the war.

Fort Nepean also fired the first Australian shots of World War II on 4 September 1939 as the freighter Woiniora, attempted to enter Port Phillip without stopping to identify herself.

Military training and Officer Cadet School

Immediately after the war, the production of young Australian regular army officers was a growing problem. Many wartime functions remained, and there was a great need for young officers. While the Royal Military College in Canberra existed, it could not meet the demand. Officials decided to establish another training facility to complement the Royal Military College, though with a much more limited scope.

The search began for a suitable location training facility. The quarantine station was considered the best site; however, it appeared unlikely that the Department of Health would allow army training. It was, therefore, decided to use the Franklin Barracks nearby, but the Lord Mayor leased the property as a holiday camp for children. After being served notice to vacate the property, the camp administrators made political representations, and the Commonwealth minister for health was asked to reconsider the question of allowing the Army to use the Quarantine Station. As a result, in October 1951, an agreement was reached for the Army to use part of the station.

The Officer Cadet School of the Australian Army occupied the site for military training from 1952-1985. Many forms of training took place, including firing live arms, infantry weapons, rockets and rifles. During the 33 years of operation, a total of 3,544 cadets graduated. After its closure, the Royal Military College at Duntroon assumed sole responsibility for training army officers.

Following the termination of officer training, the School of Army Health used the facilities from 1985-98 when it was transferred to Bonegilla.

During the Army years, the hospital buildings were used for Junior Ranks Club, cadet accommodation, Quartermaster’s store and canteen. The Regimental Sergeant Major occupied the shephard’s hut building with its commanding view of the parade ground.

Transition to public heritage and a living monument to resilience

For much of its history, Point Nepean was closed to the public. This changed in 2009 when the Victorian Government incorporated the site into Point Nepean National Park. Visitors can now explore over 50 preserved buildings and experience the unique blend of quarantine and military history that defines the site.

Point Nepean is a testament to Australia’s efforts to protect public health and national security. Its rich history, from isolating disease to defending the coastline, offers valuable lessons in resilience and adaptability. Today, it serves as a cherished cultural and historical landmark, ensuring that the stories of those who passed through its gates are not forgotten.

Good read Robert.

How about you reconstruct the early quarantine story for Brisbane: Dunwich, then Peel Island (also a lazaret or leper colony), thence finally located at Lytton.

Gary

Gary, I have read a little about Lytten, but I don’t have much information. I have been meaning to write the Point Nepean story for quite a while after collecting quite a bit of information about it, as we visited the area at the end of 2020 and spent a fair bit of time there.

Excellent read.

Another interesting and important story of Australia’s past. Thankyou Robert.