In this penultimate Surrey Hills blog, I have the privilege of providing a deeply personal story from Brian Rollins about his association with Surrey Hills.

While I provided a shorter, more sanitised version of Brian’s Surrey Hills involvement in Chapter 13 of “Fires, Farms and Forests” under the heading Soothing the Soul and Raising Awareness of Early VDL Co. History on pages 189-91, Brian‘s blog surpasses that and takes us into his soul and purpose during a tumultuous time in his life.

He shares the harrowing experience of outliving a child and how that experience changed his life and introduced him to Surrey Hills. It is a very intimate journey that makes compelling reading.

Brian is an excellent writer, and I am sure you would agree after reading his story.

It all began with the Surrey Hills.

Whenever I hear the name or otherwise think of it, I am instantly transported to a place of relative contentment and peace of mind. It’s like going home.

Four decades ago, when I began my intimate association with that vaguely defined frontier land between north-west and west coasts, my mind was in no such positive place, the future uncertain.

In November 1984, after a 15-year career with a private survey practice, I accepted an offer of a 2-year contract with the DMR, opening two new link roads to the west coast. That decision was made not without apprehension – trading secure for insecure, a single-income household, with mortgage – it hadn’t the hallmarks of stability. But being very unsettled, I felt a desperate need for change.

In retrospect, it was probably the best and most far-reaching decision of my life.

If we are indeed fortunate, the unforeseen can precipitate a legacy of life-long love. And, conversely, a decision made in love can cast a life-long shadow.

The catalyst for my change in career direction was an event which occurred a year earlier, in late August 1983. To me, this event was the equivalent of an asteroid passing close to Earth and being flung forever from its former trajectory.

Late one night I was sitting up alone with my nearly eight-month-old daughter Stephanie when she suddenly died in my arms. The family doctor had seen her at lunchtime, and even though she was exhibiting no change in symptoms when I arrived home from work, I had developed a growing and awful sense of malaise that I could not shake off. Giving Stephanie the benefit of the doubt, I decided to sit up with her rather than go to bed; I could never have slept anyway.

The stunning surprise of her death literally sent me into shock. Coming out of it was like gradually finding the way out of dense fog. Part way through I became aware of my anxiety about how to apply CPR to an infant, as I had never before been called upon to apply it even to an adult. Having laid Stephanie on the carpet, and kneeling over her just about to apply the first compression, I heard a voice saying ‘What on earth are you doing?’ Acknowledging my subconscious, I sluggishly thought ’Yes, what am I doing?’ I had never envisaged myself in this invidious position – it hit me that I had a horrible life-defining decision to make. That sobering realisation evaporated any remnants of haze.

There was no time for a quick cuppa and deep thought, there could be no second-guessing, so in the next 20 seconds or so my mind flitted over the salient events of Stepanie’s short life – her birth by caesarian with an undiagnosed life-limiting condition; her RFDS flight to Hobart before she was a day old; the long drive down only to learn from the consultant paediatrician that ‘on a colour scale from pure white to jet black Stephanie is very much in the black’; a terminal diagnosis that might come to pass within the next couple of weeks, but certainly not later than infancy; the recommendation her medical file be marked ‘Do Not Resuscitate’; her eventual return to the Burnie Hospital, and then home for the first time; the two occasions we had saved and prolonged her life by applying the same standard of devotion (that the medical fraternity did not expect of us) due to her two-year-old brother, all the while knowing there could be no miracles.

As I came to the end of my detached reappraisal, I realised how fortunate (a very sharp double-edged sword!) I had been to have been present and holding her at the time of her death. That is a rare circumstance for anyone who loses their child. If I managed to bring Stephanie back from where Mother Nature had taken her, there would be a next time, and the chances of me being present were exceedingly small. That was my final thought before deciding that now was the time – to give up, stand up, and back away – to abandon her, the little daughter I had always longed for. That decision would have been different had Stephanie, like her brother and younger sister yet to arrive, been born with hope.

When I say ‘give up’, that only applied to giving care, not love; the loving has never stopped. Stephanie lives within, and is honoured and remembered each and every day, and here, and now.

Stephanie’s legacy looms large. If I was destined never to forget the evening she departed, when my instincts wrestled with reason, I was doomed never to forget the date. It was a couple of hours later, in the early hours of the next day, that it dawned on me Stephanie had died on my birthday, the day I turned 32.

The previous eight months had been torment; her final moments traumatic, but I knew enough of life to appreciate the aftermath from Stephanie would exact a toll, and not just on anniversaries, but I hadn’t the slightest idea how that would play out. Within a couple of weeks, I recognized I had changed, and was still changing. I had been ‘nuked’, my psyche seared, a pain-rimmed hiatus created within that is ever tender. A void, a vortex, ever vigilant for weakness, and ever ready to draw me into its depths of pain and sadness. With the 24/7 media delivery of details of death and destruction, mayhem and misery, even forty-one years after Stephanie it still requires constant attentiveness to state of mind to find the means to resist.

We are not blessed with the ability to see the way ahead through unlit darkness. If life was merely a pair of divergent paths, we could only guess which might offer us the most favourable future. Somehow, good fortune lay ahead on the path I chose.

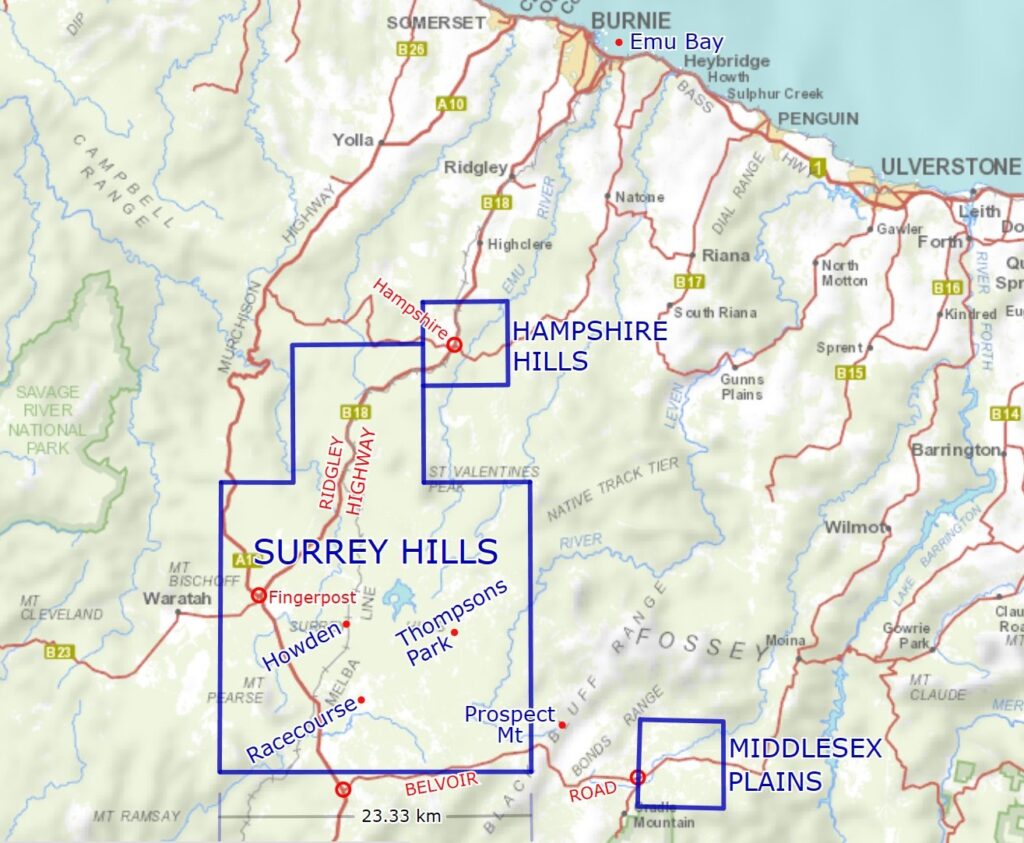

When I commenced my work with the DMR in early January 1985, I was a couple of months behind the construction crews operating on both roads, the Guildford (Fingerpost) to Hampshire, and Cradle to Que River Link Roads. The former is now the southernmost section of Ridgley Highway, and the latter is now known in its entirety as Belvoir Road.

A new job, unfamiliar systems, two roads 54 kilometres in length largely through bushland, multiple fronts of operation, around-about means of access between each, an engineer or supervisor or two, varying numbers of foremen, many heavy machinery contractors being paid by the hour and not to be left idle, half a dozen or so crews of newly employed ‘peggers-out’ (some of them inexperienced) and no system (from the survey perspective) of having everyone singing from the same hymn book. If everyone had been left to do their own thing, it wouldn’t have been long before serious problems arose. Time was the main issue as I could not manage all my own field work and the simultaneous need to prepare a set of procedures – as I had come to interpret them – that everyone involved (engineers and foremen especially) could accept. That required many of my midnight hours.

As the first year progressed and was consumed by the multitude of tasks, things gradually settled more comfortably into place. As I went about my work, and travelling to and from it, I had begun to notice the effect the natural environment was having on me. In my former job as survey practice manager, I was dealing with hundreds of clients a year, with diverse needs, and in locations from one end of the coast to the other. The main point in common between these clients was they required work on land that had been developed, long since converted from its native state, whether in town or country. There had been no real connection to country.

The bush work component for some of those clients had usually been enjoyable, but it was certainly more physically demanding. Most bush on the fringes of agricultural land had been left in its natural state for one reason only; it was too ‘topographically challenging’ for agriculture.

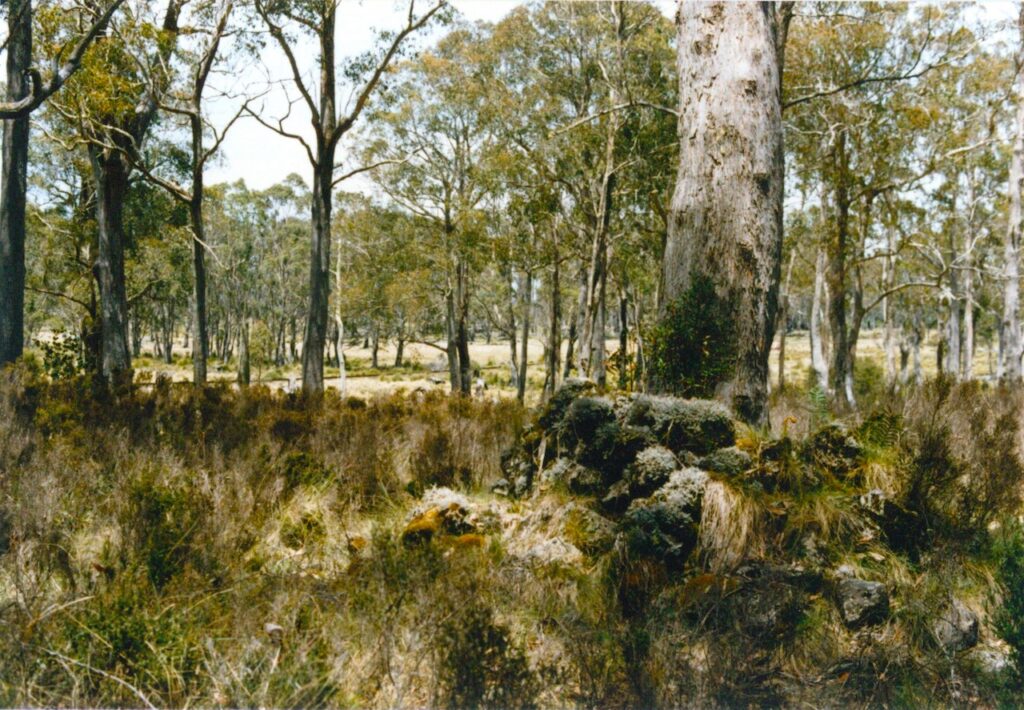

But in the Surrey Hills what appealed most to me were the patches, often large expanses, of native grassland or open eucalypt woodland that appeared to be still in near-original state. White man’s presence had left little or no visible impact. It was almost as if there was still country that time had forgotten, and so close to ‘civilisation’. This near-natural environment began to work in my mind. It was not necessary to traipse rugged mountain ranges or National Parks to appreciate natural beauty.

My after-hours pursuits could now turn from work to contemplation of the local history of the area in which I was now immersed. A handful of years earlier Chris Binks had published his book ‘Explorers of Western Tasmania’ and I enthusiastically absorbed the sections involving the Van Diemen’s Land Company and their activities. In fact, that book was the only one of mine to succumb to the fate of losing its dust cover through disintegrating from over use. For some years I had been saving newspaper articles on our local history by writers such as Wilf Winter and Kerry Pink, so I obviously had a natural curiosity. Understanding the history of an area is enriching, just like comparing a black and white image to the same one in colour, but there was never any thought or motivation of moving beyond a passive interest.

This was a survey with a difference – not only huge land parcels, but a property survey with boundaries calculated from a triangulation network, a rarity. To put ‘huge’ into some context, the longest boundary, the southern boundary of the Surrey Hills Block, was 14.5 miles (23.33km) long.

A cursory inspection of Sprent’s plan showed two of his survey stations straddled the new road as it crested the Black Bluff Range – one at Rocky Mt and the other at Bare (now Prospect) Mt. A scale rule, protractor and calculator were all it took to work out general locations for a site inspection, when time and work permitted. Should either be found, they could be connected to the survey of the road corridor.

The day eventually arrived, and my chainman Kerry (‘Stretch’) Taylor and I set out on the 2½ km cross-country walk along the top of the world towards Black Bluff. After a while we could perceive a pimple on the bare summit of Prospect Mt, which soon enough resolved itself into a rock pile. The time was approaching the 11th hour, of the 11th day, of the 11th month, 1985. Remembrance Day. As my watch ticked over the appointed hour we quietly stood beside the cairn and I remember facing Cradle Mt, with the rockpile at my feet, and paying respect to the fallen, including my great uncle Viv Rollins who died at Passchendaele in October 1917. I also remembered the little girl whose life lost was the catalyst for taking this job. Had I not done so, I would never have found this 1842 survey mark, the oldest by far of those I had previously found during my career. A connection had been made in my mind. But little did I then realise that in one month’s time, a passion would be born out of my discovery that will endure for the rest of my life.

Serendipity. Perhaps the loveliest word in the language. The morning AFH Property Officer Bruce Hodgetts drove by, ten days later, was just that. On 21st November, while we were carrying out survey control on the Cradle Link Road about a hundred metres or so west of its intersection with Murrays Plains Road, Bruce (with Noel ‘Yogi’ Wells, Hampshire Gate-keeper) tootled by on Murrays Plains Road in his red Toyota Landcruiser. Of the 54 km length of link roads, with multiple intersections with pre-existing roads, Bruce just happened to pass by this particular one, on this particular day, at this particular time, and within easy hailing distance. Time for a catch-up and a cuppa.

I had first known Bruce in his days as AFH surveyor, way back in the summer of 1968/69 (I think it was). It may well have been the fond memories of that matriculation holiday work as one of Bruce’s chainmen working in the Surrey Hills that indirectly landed me in a surveying career.

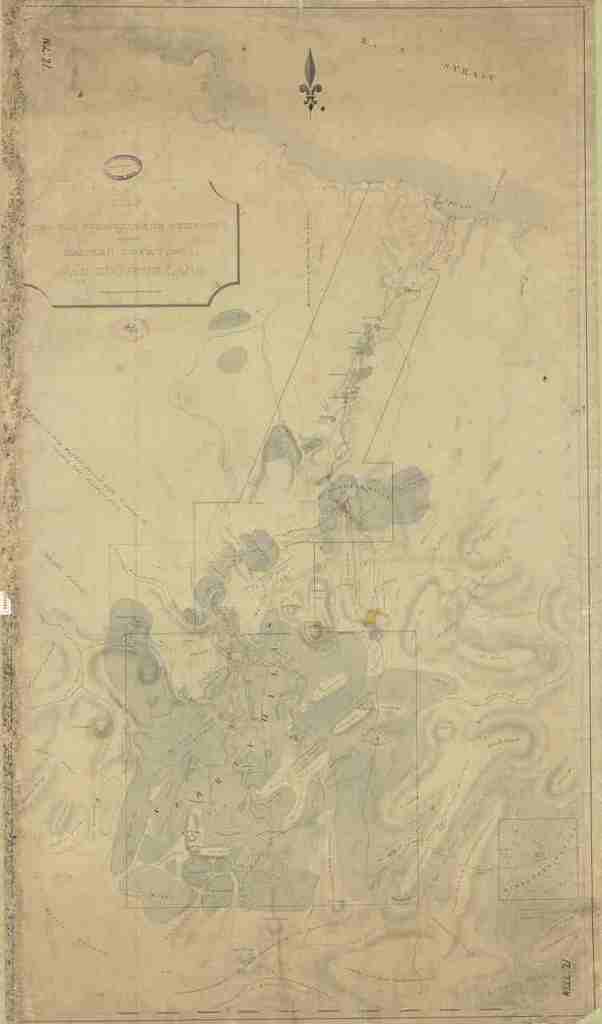

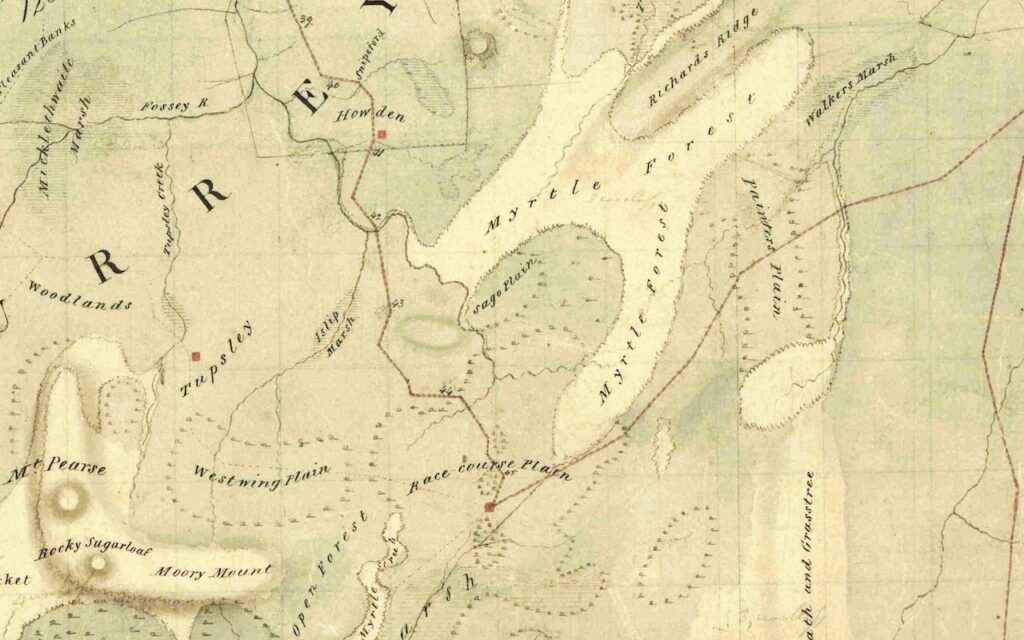

Eventually our conversation turned to the old 1842 mark of Sprent’s we had found up on the Black Bluff Range. This prompted Bruce to retrieve a box-file from the back of his bus, and from it he extracted negative photostat copies of some old plan of the Surrey Hills. Being in multiple sections, it was rather difficult to read and interpret, and it had not been copied in its entirety. The date and author could not be found, but the bottom half of its Lands Department reference number was evident. Luckily this could be interpreted and a day or so later I posted off a search request for a copy of this plan so I could peruse it at leisure.

A set of A3 copies eventually arrived, but, rather ironically just as with Bruce’s copies, the original plan had not been fully copied, only the area around the Surrey and Hampshire Hills. To a Registered Land Surveyor, a plan or survey is not just an item of interest – it is a piece of evidence in a larger pattern, one piece of a complicated jigsaw puzzle. To be fully understood any plan must have a wider context than geographical place alone – it must also demonstrate its place in time – without its date and authorship it only had curiosity value. I was still no wiser than Bruce.

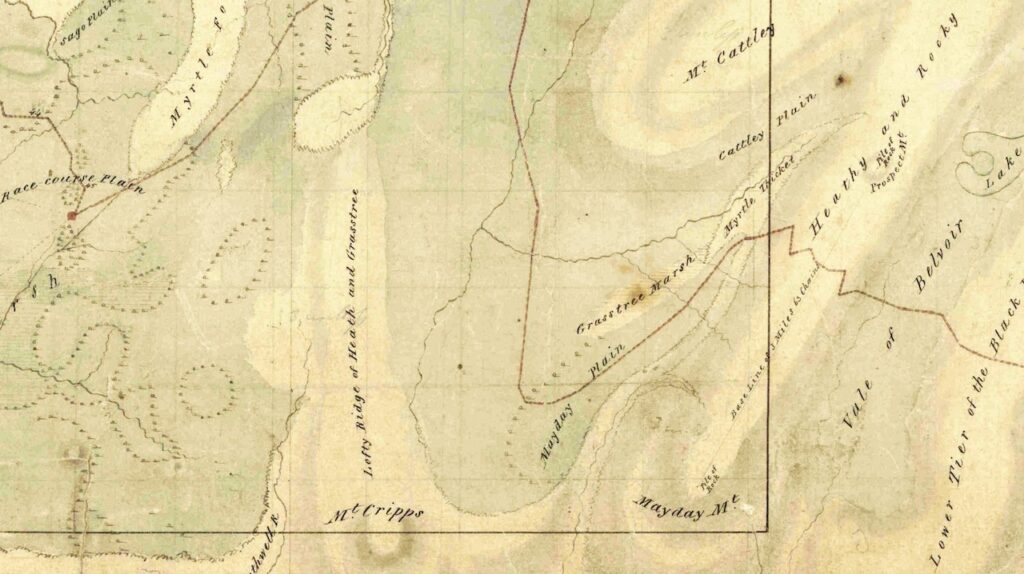

One of the features of this plan was the description ‘Pile of Rock’ on the summit of ‘Prospect Mt’, a little to the west of Lake Lea. This was in the same relative location as Sprent’s triangulation station on his ‘Bare Mt’. The author of the unknown plan had obviously been aware of Sprent’s survey work, and found his survey station, even though a name change had occurred. As the name ‘Prospect Mt’ is still in use, it was reasonable to presume the unknown plan post-dated Sprent’s.

While my curiosity had not been satisfied, the plan was of no real professional value as it did not show full boundary dimensions or evidence of same. Disappointingly, I put it aside and didn’t bother to harass the DMR search clerk by putting in a third request.

I had almost put it out of my mind, but something about the plan niggled me and wouldn’t leave me alone. It would only continue to pester me unless I knew the full picture, so some days later I decided to send off my third search – this time for a COMPLETE copy, please!

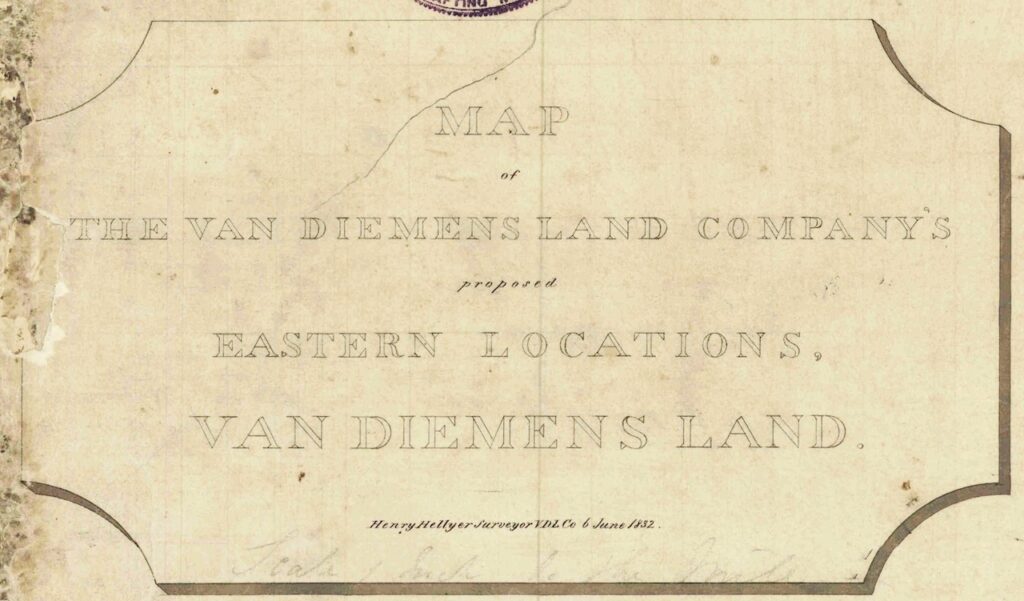

When I arrived home after my last work day before the Christmas break 1985, there was a large envelope waiting for me. Opening it and looking at the top page with title block – appropriately highlighted green by the search clerk – I was totally surprised to see the author of the plan was none other than Henry Hellyer, and dated 6 June 1832, a few weeks before he took his own life. The rockpile on Prospect Mt was his. This was an astonishing discovery! Hellyer had been a surveyor in private employ; there was no reason to expect a plan of his to be registered in the Government’s Lands Department.

The limited number of Hellyer’s maps I had ever seen were all in Chris Binks’ book, and these were small sized, small-scale maps of the north-west, nothing particularly detailed. Those maps were of an era that had previously seemed so remote and unapproachable. The unearthing of one of Hellyer’s last plans, one that was large scale and potentially accurate and useful to another surveyor, brought with it a realisation. With the fresh memory of having stood before Hellyer’s rock pile on unchanged Prospect Mt, I might just as easily have been standing there the best part of two centuries earlier; time was indeed relative. I had at my disposal the equivalent of Dr Who’s Tardis. If the rock pile had survived there in the back-blocks since pre-1832, perhaps also some other features of Hellyer’s plan? But before I could know where to search, there were many, many midnight hours in store for me.

The search for relics on country was, simplistically speaking, reverse engineering of Hellyer’s plan and was briefly described in an article published in The Australian Surveyor of June 1988.

Over the course of my second year on the Link Roads as my study of the old road alignment was completed, and my appreciation of the Surrey Hills grew, when time and proximity allowed, my multi-faceted ground search began and was often quickly fruitful. Finding some of those old relics as mapped by Hellyer, previously unknown, are magic moments in my life.

Howden exemplifies one of those moments, and demonstrates how the author of the two-centuries old plan can still communicate across the years with someone able to interpret on-ground topography, on-paper linear representation, and the intent of the original hut-builder.

Having marked up Hellyer’s road to Racecourse Plain and the predicted Howden hut site on my copy of the Inglis 1:100,000 Tasmap, I was pleased to see that although the nearest road was about 750 metres away, the hut was only about 100-150 metres west of the Emu Bay Railway Line. The railway post-dated Hellyer by six decades. Parking near the rail crossing on Clipper East Road, ‘Stretch’ and I set out to pace north along the railway. Accurate pacing along a railway line with exposed sleepers standing proud of the ballast is difficult; a crying shame their spacing is not a regular metre! Nevertheless, it was better and quicker than the same exercise following a compass bearing through light bush.

Two-thirds of the way there, we crossed a creek not featured on our modern map, yet was shown on Hellyer’s. Then, everything started to fall into place. Looking ahead a couple of hundred metres on the left, roughly our intended destination, was a gentle rise – a perfect spot for a hut – elevated, dry, with some security, and a water supply close by. We carried on, but no longer counting our paces, until we arrived opposite the likely spot. Then, a 90° turn, and off towards the west. Cresting the gentle rise in front of us lay a high mossy green mound.

Without one wasted step we arrived at the detritus-encrusted stone chimney butt of the old shepherd’s hut, the square edges of the fireplace still perfectly preserved on its southern side. It wasn’t difficult to imagine the original inhabitants of the late 1820s standing exactly where we were before the fire, kept ever-stoked by the hut-keeper, warming their hands in winter or boiling the billy in all seasons. It was almost as if the long dead surveyor and his plan were talking to me – ‘look for the smoke’ – yet that chimney hadn’t seen fire since about the time Hellyer had taken his own life. When George Augustus Robinson passed by two years later on 16 June 1834 he recorded in his journal – ‘…passed a deserted hut at Howden; this station is forty one and a half miles from Emu Bay’.

With experiences like that it is little wonder the Surrey Hills had sunk its hooks into me.

But all good things come to an end – time moves on, and it was time for me to move with it. At the end of 1986 my contract with the DMR was due to expire and my career needed to change direction yet again. However, I wasn’t at all comfortable leaving the Surrey Hills; they had come to enthrall me and I was unwilling and unable to withdraw the hooks keeping me tethered. For six months I felt a kind of home-sickness as my new role kept me away from the attractions of that sub-alpine plateau.

But my love for Surrey continued, even if I didn’t have the luxury of working there on a daily basis. I can’t remember the details now, but somehow in days past I was always permitted access and a key to visit as I pleased, and continue my historical research.

My curiosity had by now been properly piqued, and I purchased an expensive pre-loved microfilm reader from Melbourne, reels of microfilm from the State Library of Tasmania’s Archives Office, and set about backgrounding the earliest days of the Van Diemen’s Land Company from 1826. Only by conducting this research could I fill in some of the space on the near-empty white board of my knowledge. Reading history books only takes you so far. As the VDL Co had interests across the entire north-west as far as the Tamar, from Woolnorth to Windemere in effect, I inevitably learned far more than just my own patch of prime interest – the Surrey Hills, Hampshire Hills, and Emu Bay. One piece of information I was able to deduce was the age of Hellyer’s ‘pile of rock’ on Prospect Mt – around May 1831, give or take a month.

I chose not to filter out the myriad aspects unrelated to the Hills; it was all so interesting and painted a much more vibrant picture of the 1820s and 30s. People, places and events are much, much more fascinating than a bland history of a company. Even today, the interest and research continues. Along the way came involvement with the Burnie Historical Society born in 1995, then multiple coach tours beginning in 1997 back into Surrey, and east and west along the coast, back to the early days of the VDL Co. Dozens of public talks to numerous groups continue to accrue, while maintaining my appetite for a history which seemingly just happened to drop into my lap. Serendipity! Thank you, Bruce.

In this electronic age, institutional memory often resides in the digital database. As senior staff of the presiding company (now Forico) move on, sometimes after very many years of service, goodwill has the potential to move on with them. It was only by their grace that goodwill was granted.

Three years ago, when it came time for my 5-year access and key-holder permit to be renewed, I was rather apprehensive. In this age of litigation, the requirement for Public Liability Insurance cover of $20m (with the associated hefty premium) was likely to sandbag my close physical association with the Surrey Hills. But I was very pleasantly surprised when the permit was issued, with the clause – ‘Additional Conditions: PLI not required, see Bryan Hayes for details.’

Bryan has now moved on. While we had known each other since his days at Ridgley, in his various roles over recent decades he had operated at a level where we never had need for contact. Yet here was a tangible expression of goodwill that is still very much appreciated, and will always be reciprocated. Those few words from the former CEO are a gift of grace, a treasure greater than gold.

Today, my collection of research material is extensive. So too my mind-map of events and detail, which together with my research notes, need to be teased out, cobbled together, and documented before my allotted time arrives. Until then, my passion is in no danger of waning. What better than the enduring tease of history, mystery and a multi-dimensional puzzle.

One such minor tease is Thompsons Park; its name post-dates any early association with the VDL Co, as none of Hellyer’s maps individualise it from similar extensive surrounds. The name probably relates to the period a couple of decades after colonization when others leased the area. What is not a minor fascination about Thompsons Park though, is its beauty and an artefact which pre-dates the arrival of white people. A very old and mature cider gum, still bearing the evidence of Aboriginal tapping of the sap, stands sentinel in this atmospheric amphitheatre of native grassland.

Of my many special places on Surrey, Racecourse Plain is perhaps the favourite. Named by Hellyer from the summit of the Peak on 15 Feb 1827, it was one of the earliest features in Surrey to receive its name, although it would be a year and a half before Hellyer set foot upon these plains. It was also the most remote settlement on Surrey.

It’s difficult to picture fine-wooled Merino sheep ever grazing here. However, on 5 February 1830, six carts drawn by oxen departed Racecourse Plain for Emu Bay with the season’s wool-clip. This was the first time Hellyer’s road was travelled from one end to the other, and four days later they arrived at the Bay where the bales would be trans-shipped to Launceston, and thence to England. This was the raison d’être of the VDL Co.

Here at Racecourse Plain on 17 August of that same year Alexander McKay told George Augustus Robinson that ‘Mr H[ellyer] he was sure would haunt the Surrey Hills after he was dead, indeed he seemed wedded to it.’ It seems more than one surveyor has fallen for the charms of Surrey.

Racecourse Plain is much more than a place alone. My favourite spot on this favourite place is the ‘lunchtime launch-pad’. On occasion I take one, two or three special guests there to commune, and this is where we pause. It is today almost as it was in the time of Hellyer, two centuries ago; perhaps even two or twenty millennia.

It is found 45 miles from Emu Bay, just after the last bend in Hellyer’s long-abandoned road before it arrived at the door of Racecourse Plain hut. It is sheltered from westerly winds by a copse of large eucalypts hundreds of years old, just as drawn by Hellyer in 1832, towering over an understory of pepper-tree. On a good day an erratic and cheerful chorus of feathered friends can be appreciated over the whispering of wind and rustling of gum leaves. St Valentines Peak looms in the distant NNE. A clockwise scan via the intermittently visible Black Bluff Range and its terminal peak, Mt Mayday (aka boring Beecroft!), Cradle Mt and Barn Bluff, brings us around to Mt Cripps in the SE. In the foreground of this engaging eyeful is a broad expanse of native white grass that first attracted the colonisers to these parts. This is only a fraction of the grassland hereabouts.

But it’s not just a name on a map. It’s not just a place where heaven and earth meet, where people and events became history. And it’s not just the beautiful environment and scenery. Stay the voices, set still one’s mind, gaze off into the middle distance, and you might even conjure a group of pre-colonial Palawa leisurely chatting and laughing as they amble on by through ancient acres of grassland. This place is elemental. It’s ethereal. It’s energising. This is one of those very special places on Surrey where time stood still, and it seeps into the soul.

Part of the enduring legacy of Surrey is gratitude and privilege. Privilege for the gift of being entrusted with access to a piece of Paradise. And gratitude, for the opportunity of having spent two beautifully memorable years working there, for what I had stumbled upon, for the absorbing and ongoing historical research, the opportunities and friendships (you know who you are) which evolved out of it, and not least – a much deeper love and appreciation of Mother Nature – and the lottery of life. Tune-out to the modern-day obsession with anniversaries; savour instead our seasons, and celebrate each day’s sunrise, and the possibilities which arise with it.

It all began with the Surrey Hills. Well, …almost. Before that there was a little girl who launched me onto an incredible and unforgettable journey in search of understanding – across country, and back through time, and into the depths of my soul. Thank you, Stephanie. Thank you, Surrey.

Going back to Surrey is going home.

A great read!

What a wonderful and poignant piece! I am part of a small group that has visited Racecourse Plains each year for almost 20 years monitoring a rare native plant, that area and the Vale are indeed quite magical!

Thank you.

A very moving telling of a personal story along with Surrey Hills history from a surveyor’s perspective.

Thank you Brian.

Thanks, Rob. Like a great many residents of Burnie – and beyond – I know Brian as a true friend. Promptly and expertly, Brian has never not answered my queries about the VDL land.

What a fantastic piece of writing by Brian. Thanks, Brian. This is a deeply stirring piece on many levels. In my suburban Melbourne home by the fire I feel that I’m back in Surrey seeing the whole area in a new, multi-layered way. Can’t wait to get back there!

Thank you Brian, much respect.

Thank you for this transcendent piece of writing Brian.

Thanks Brian.

Surrey Hills is a beautiful place and your passion only reinforces that beauty.

Thank you, such a fabulous read of a very personal

journey.

I was a dozer operator for North Forest Products and I dozed the track from the Murchison Highway to Murray’s Plains Road for the surveyors.

Sensational read Brian. Vicki and I had the opportunity to go on one of your bus tours to this wonderful place. It was an amazing opportunity to listen to you and follow Hellyer’s Road.

Cheers Rob Vernon.

Excellent piece Brian, thank you.

Thank you Brian for sharing your story with us.

Dear Brian, thank you for such a poignant and personal account of your life and travels.

I remember a bus trip you hosted many moons ago now, ending in Highfield House. What a wonderful experience that was.

While reading your story, I was walking with you and I have never been inspired that way before.

Thank you also Robert for including this in your blog.

Thank you Brian and Robert.

Beautifully written by Brian and warmly evocative.

Your passion for Surrey Hills is writ large in your story. It is well understood by all of us who have had the privilege of spending quality time on this wonderful estate.

I am very happy that Brian and Roberts’ outstanding historical and literary work means that history is not lost when the rest of us move on.

Gratefully yours, Bryan.

Thank you Brian for sharing your passion for Hellyer and Surrey Hills with us.

A great read. More than just about the land.

Regards Simon.

A further footnote to Brian’s beautifully written ‘Surrey Hills’ essay.

In the summer of 1958 David Dickenson, (Chief Surveyor-AFH) and I, and two of the company’s top equipment operators at that time; Gordon Bester and Clarry Murray plus their D7′ bulldozers, set up camp out on Murray’s Plains so as to re-establish some of the south boundary of Surrey Hills, which had not been done since the early 1900’s by the then VDL surveyor Mr. Blackwell. At that time discussion was already taking place in state government circles regarding development of a highway linking the Cradle Mountain Road to the proposed Murchison Highway, across the Vale of Belvoir and AFH Manager Reg Needham wanted to ensure that the property boundary was well defined and up to date so as to fully protect the Company’s interests.

David was a meticulous surveyor and he ensured that the dozed trail paralleled the legal survey boundary only, in order to protect any historic evidence of earlier survey work. There was some hope at that time of finding evidence of Henry Hellyer’s original survey marks, but none were found. However, we did find several of Mr. Blackwell’s ‘flatiron’ axe marks on some very old myrtle trees.

Barry