“It doesn’t matter what is true, it only matters what people believe is true.“[1]

Before I started our travels, I recall hearing and reading stories about the parlous state of the Murray River and its basin. These calls are always louder when there is a drought.[2] On our trip, I have spent a lot of time on the Murray, the Lachlan and Edward Rivers, as well as in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation area. We also stopped at Wentworth to observe the mouth of the Darling into the Murray River. During my visit, I didn’t see any signs of a river system in peril. The biggest clue about the functioning of the whole ecosystem is not found at the inland rivers but in the black soils bordering them. They are some of the richest soils in the world, resulting from millions of years of erosion and deposited on the plains. They didn’t wash down the rivers out to sea. Adding water to these soils through controlled irrigation allows the production of food crops year-round at a scale to feed the vast increase in the world’s population.

When explorers John Oxley and Charles Sturt visited the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) in the nineteenth century, they described the treeless plains as unsuitable for habitation. And yet, we see 200 years later towns and settlements supporting the most productive farmland in Australia, which belies their observations. Settlers, farmers and irrigators have transformed the dry, arid lands. For example, the rice paddocks in the Riverina have been the most efficient and productive globally. At the same time, they have become the most extensive frog-breeding area in southern Australia, also supporting an abundance of wading birds. Irrigation is a very efficient way of producing food and fibre. It occupies just five per cent of tillable land but is responsible for over 35 per cent of production. Without it, there would be a need to farm more ground with less reliable water supplies for the environment and river communities.

But we are continually told our rivers in the MDB are dying, and it is the irrigators fault.

Journalist Margaret Simons used hyperbole in her recent polemic essay on the MDB. She best sums up the shrill about the river dying:

“Over the latter part of the last century, it became clear that the river system was at breaking point. It could die. All that went with it – money, livelihoods, sense of nation – was at risk. There were many indicators, including salinity, blue-green algae, fish deaths, and the Mouth closing. There were billabongs that smelt of rotten eggs”.[3]

If we look at the ‘indicators’ mentioned by Simons, it becomes evident that the management and politics of the MDB are based on several fabricated myths.

The Murray myths

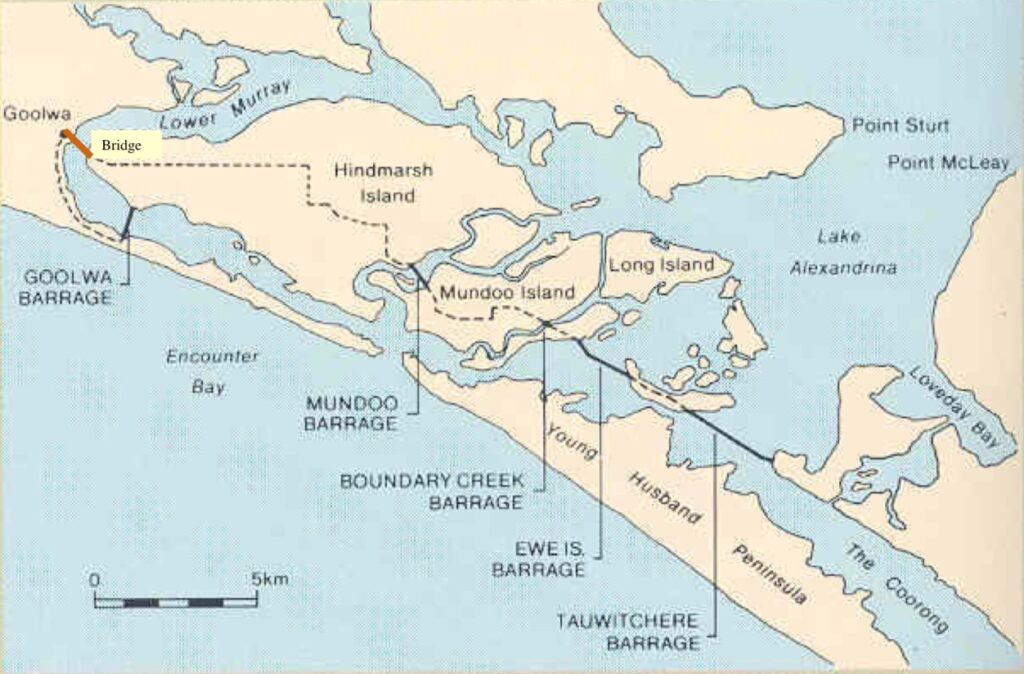

The first has to do with the mouth of the Murray River, Lake Alexandrina and the lower lakes. It is assumed the Murray River’s mouth is at sea and that Lake Alexandrina has always been a freshwater lake. All wrong.[4] The Murray has changed the position of its mouth on at least three occasions in the last 30,000 years. The entrance and exit to Lake Alexandrina have changed. The lake was once a wonderfully productive area. Aborigines treasured the lake for the big mulloway that they caught in it. The long, narrow stretch known as the Coorong and the many swamps of the south-east of South Australia were a feeding and breeding ground for lots of water birds. It was flushed for millennia by tidal waters, not freshwater. Since settlement, the swamps were drained, and the Coorong is now little more than a stormwater channel. Five barrages were constructed in the early 1940s across each channel connecting the lakes with the Coorong and the ocean. These barriers restricted tidal flow into Lakes Alexandrina and Albert and stopped freshwater from flowing out. It created an artificial freshwater system and constant water levels. The lakes no longer harbour much fish. To demand a large additional volume of valuable irrigation freshwater to do the job that nature did with seawater displays a total ignorance of history.

The second myth is that fish deaths result from a lack of environmental flows and over-extraction by irrigators. The media widely reported recent fish kill events in December 2018 and January 2019, with an estimated one million dead fish in the Darling River. The cause of death was the stratification of the water column in the weir near Menindee, which led to blue-green algae attacks in the warm surface water during a run of sweltering days. A scientific panel blamed drought and over-extraction for the lack of river flows. While the scientists acknowledged there had been fish kills during other droughts, they argued that this event was ‘unprecedented.’ However, they didn’t provide evidence to support their claim.[5]

After a quick ten-minute online search on Trove, I found references to similar fish deaths on the Murray and Darling Rivers, proving that the 2018-19 event was not unprecedented. For example, the media reported fish deaths in 1902 on the Darling River at Bourke during the Federation drought.[6] Thousands of fish “of all kinds, up to large cod, had been dying for several months” between Wilcannia and Bourke in 1929.[7] It was believed at the time that when the Darling River was at low levels, it was brackish and contained minerals, coupled with the draining of stagnant water from pools upstream, “fouled the water so much that fish could not live in it”.[8] When a ‘fresh’ came down the river from its upper reaches, “no fish are now dying”. Similar fish kills occurred when the river was low for any length of time. In 1938, hundreds of silver bream were dead on the Murray near Mannum, ranging in weight from an ounce to two pounds.[9] In 1941 thousands of fish died between Lock 11 upstream to a mile above Mildura and washed up on the Victorian bank of the Murray River.[10] In February 1951, there were reports that the “Darling River smells of dead fish”. Near the river’s edges were thousands of dead fish, including Murray cod weighing up to 20 pounds. Subsequent analysis found their stomachs and mouths were full of undigested shrimp.[11]

The third myth is floodplain harvesting in the northern Darling River basin is detrimental to river flow and constitutes water theft, as it is not regulated. The flood plains across Australia, specifically in the MDB, are unique and do not follow the usual floodplain-river relationship. The actual level of the floodplains is situated below the riverbanks. Water flows out and away from the river across the land. The slope is very gradual.

In contrast, the hills and slopes above the floodplain feed the rivers, fed by runoff from the mountains, tableland, and plateaus. So, after flooding rain events, when the riverbanks spill water onto the plains, about 40 per cent of water can only return to the river, which is during significant flooding. The vast majority of the water sinks into the soil or evaporates. The little water that any farmer can harvest, when available, is very small compared to the overall volume involved. Even if not harvested, the floodplain water has little to no bearing on downstream flows or levels. The harvested water is retained on the plains, as that is where it is used. Critics of floodplain harvesting always overlook that floodplain water is only ever available after a flooding event. They also lump it in with over-extraction issues, and sadly, it pits farmers in the southern irrigation area against those in the northern basin. The other fact about the Darling River not widely known is that it only contributes less than six per cent of the natural flow of the Murray River and is the most highly variable flow of all the catchments. Being an unlikely water source, one wonders why there is such a focus on this catchment concerning environmental flows.

The fourth myth is the assertion that the native Murray cod is disappearing. Europeans have thrown everything at the Murray River by highly modifying the water flows. Scientists from the Cooperative Research Centre produced a report, ‘Fish and Rivers in stress: The NSW Rivers Survey’ in 1997. They considered it the most comprehensive survey of fish in the Murray, even though it provided no data to determine trends in fish numbers. The report concluded that despite intensive fishing with the most efficient sampling gear, for a total of 220 person-days over two years in 20 randomly chosen sites, not one cod was caught. However, not long after, fishing magazines and results from local fishing competitions showed a different story. They reported a harvest of 26 tonnes of Murray cod from the same region as the scientists![12] The fishermen I talked to on my travels all referred to catching large Murray cod and that they were still definitely in the river.

The fifth myth is that farmers own the water. They don’t. They have obtained licences to extract or have water delivered at certain times. In New South Wales since the 1920s, allocations have been determined each year on the following priorities – the first for river flow and interstate agreements, such as supply for South Australia; the second for stock and domestic use for towns along the rivers; the third for permanent plantings such as orchards and vineyards. What’s left goes to the remaining licence holders. State authorities have always owned the water and could send any flows they wished down the system.

The storage and regulation of river flows

The Murray River and its tributaries are an ancient system. The source of the Murray itself was defined 20 million years ago when rushing water from eroded mountains flowed onto a flattish plain and covered it with layers of sediment on top of a deep deposit of salt that was a sea before that. Lakes, billabongs, lagoons, and swamps act as settling ponds and filters along the MDB path. Particular aquifers drained salt from the system. These drains relied on the rivers dropping to low levels periodically to be effective, increasing the salt levels in the remaining water. The salt was then flushed away by the next flood.

The unique flushing system has been rendered useless by the changes since European settlement. Over the last 120 years, many dams and locks have been constructed on the Murray to ‘drought proof’ the river and provide a reliable supply for irrigators to create a food bowl, essentially harnessing the MBD for economic use. It all started in 1914 when the Commonwealth government and South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales were forced to act and agree on the cost and water sharing. It followed 13 years of negotiation, which came to a head during the 1914-15 drought when the Murray River became a trickle. Finally, they agreed on South Australia’s entitlement flow, a primary storage on the Upper Murray (the Hume Dam), Lake Victoria storage, 26 locks and weirs between Blanchetown and Echuca, and nine locks on either the Darling or Murrumbidgee Rivers. However, because the industry of boat navigation along the Murray declined, only 16 of the originally planned locks and weirs were completed.

There is around $2 billion worth of assets built on the Murray River between 1913 and 1979. Irrigated wheat, cotton, grapes, almonds, citrus fruits etc., are grown on land once covered by saltbush. A consequence of all this storage is that the water level in the main stem of the Murray is unnaturally high, most of the time. Without any proof whatsoever, several ecologists claim that dams destroy rivers. They don’t. They enhance the river environment. For example, without Burrendong Dam, the Macquarie Marshes and nearby wetlands would be in a much worse state, Dubbo would not support 36,000 people, and high-value crops could not be sustained in the Macquarie Valley.

The natural history and these modifications are quickly forgotten or ignored when the management of the entire water system is dictated by partisan political fighting between states. Caught up in the maelstrom are the irrigators. Leading the attack has been environment groups who have sponsored scientists to develop strategies to increase ‘environmental flows’ based on a lack of accurate scientific data. The partnership between scientists and the environmental groups has successfully lobbied the government and convinced the public the Murray River is in crisis and is dying. Every drought cycle, we hear the same. Every subsequent recovering flood cycle, the river bounces back, and the media ignore the MDB. Over these cycles, we are never told what improvements have been made by irrigators who have embraced environmentally friendly technologies and practices.

The damming and regulation of the water flow in the Murray is nothing new. For centuries humans have been meddling with water to survive and grow crops to eat. The Mesopotamians were the first people to channel water across mountain ranges. After that, the system spread across Africa and Europe.

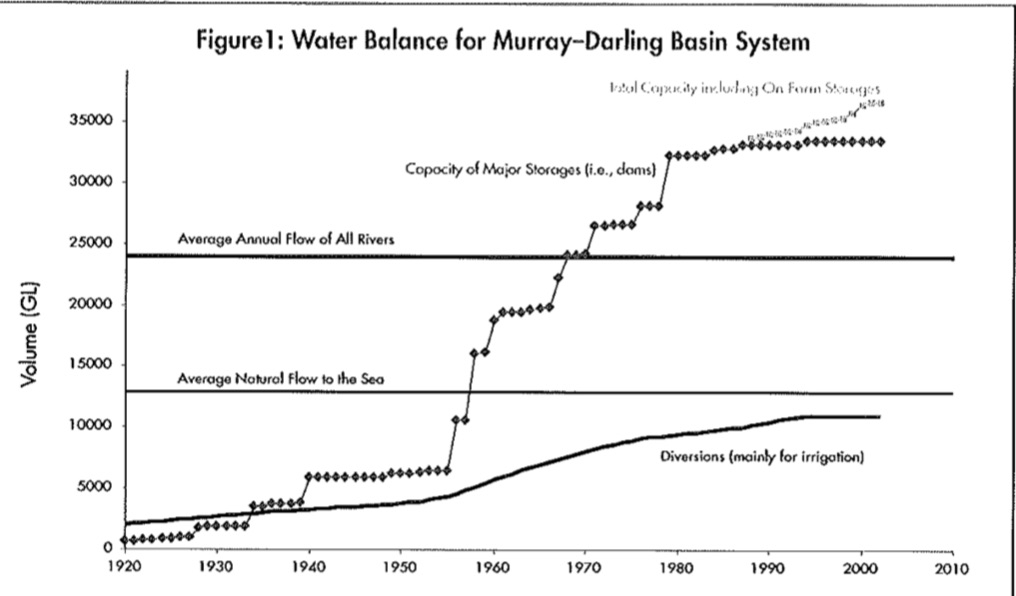

When the MDB system is stressed at every drought cycle, there is always an emphasis on the amount of water extracted by irrigators. Figure 1, shown below, is not readily available and was used in a report by scientist Jennifer Marohasy.[13] It showed that the system’s storage capacity was about 53 per cent more than the annual average inflow. The percentage of the total capacity used by irrigators was about 18 per cent. However, storages are rarely full, so the figure closer to reality for irrigation use was around 24 per cent.

The inflows in the MDB vary each year considerably depending on environmental conditions. A computer model was developed that estimated the total water balance for the Murray River based on a hypothetical average year under natural conditions (without dams etc.). In an average year, the total inflow was estimated at 12,607 gigalitres, where 24 per cent was lost through evaporation, 34 per cent was diverted for irrigators, and 41 per cent flowed down the river. But if you read the government reports, mainstream media and listen to environmental groups, you would get the impression that irrigators take 80 per cent. According to Marohasy, the 80 per cent figure appears to have been calculated by variously combining losses and diversions and calculating medians rather than averages, giving the impression the basin has been ‘drained to death’.

The work by Marohasy and fellow scientist Lee Benson, who both argued that the MDB was in a healthy state, was vindicated by a Commonwealth Government inquiry into ‘Future Water Supplies for Australia’s Rural Industries and Communities‘. The Inquiry’s 2004 report concluded that the MDB rivers were in good health, and the science was so poor it could not justify water being taken from production.[14]

According to Chairman of the Mid-Murray Citrus Growers, Neil Eagle AOM, “Marohasy and Benson completely dismantled the false information of dead and dying rivers peddled by a group of Australian scientists calling themselves the Wentworth Group. In a television interview, the late Professor Peter Cullen, the lead proponent of the Wentworth Group, admitted that ‘well, yes, the rivers are in quite good health’”.[15]

The 2004 Inquiry report was ignored due to the successful lobbying of the Wentworth Group, and the decline in river flows from the millennium drought was blamed on the over allocation of water to irrigators.

The obsession with environmental flows

The Wentworth Group framed the basin-wide plan and its priority for environmental flows.[16] They suggested increased environmental flows of 1,500 gigalitres (the equivalent of three Sydney Harbours full of water) could be achieved by irrigators voluntarily giving back ten per cent of their water allocation. The remainder was to be bought by the government. This all followed the 1981 drought where the alleged Murray mouth closed. The management of the MDB changed its focus from just water resources to include the land and the environment under the auspices of the MDB Ministerial Council.

In 1987, with Labor governments in power in South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and the Commonwealth, a Murray-Darling Basin Agreement was signed. It was believed then that because the Murray River’s mouth closed, the quality of water was poor, and so were the wetlands, and it was the fault of irrigators taking too much water from the system. Visible signs are powerful. In the early 1990s, a toxic blue-green algae bloom infected more than 1,000 kilometres of MDB rivers. The shock of seeing this poisoned water meant that it had been over-allocated. That event led to the Murray-Darling Basin Commission (MDBC) who began capping extractions in 1995.

The rationale behind capping water extraction was that the ability to trade water meant it would go to the highest value use and be more efficiently utilised. In 1994 the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to a water reform process to achieve a more efficient and sustainable water industry. These included catchment-based plans to underpin water allocation and to direct appropriate environmental flows. Also considered were water property rights and trading issues. Water licences were initially attached to the land. They were progressively unbundled so that separate water trading could be encouraged. For example, you could own land and sell the water licence that belonged to it. Or you could own a water licence without owning the land. Not only that, water licences could be moved from one valley to another.

In the 1990s, a report by ABS was published and stated that environmental degradation increased as water diversion had increased. No data was provided to support the claim; simply, it was correlated that river health was linked to water diversion. Blue-green algal blooms had occurred before the river flows were regulated. Records of blooms are known from 1853, 1878, 1880 and 1888.[17] A Conference in 1930 recognised the outbreaks of blue-green algae as a natural occurrence. Blue-green algae favour stagnant waters, and they have found their way into the main channels since extensive water levels have risen between locks.

In August 2003, in the lead up to the COAG meeting, the Wentworth Group released a paper titled ‘Blueprint for a National Water Plan’ funded by the World Wildlife Fund and supported by CSIRO to give it some form of scientific legitimacy. However, its many claims were misleading, including one of which I am familiar with as a forester – the claim that the river red gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) are dying due to depleted river flows. The Wentworth Group relied on a visual assessment by the MDBC in the middle of the millennium drought. The MDBC’s report contained a stand condition model using satellite imagery to assess tree health. No field verification work was carried out.

The best way to show a decline or improved tree health is to assess the same trees, or a random sample from the same group of trees, at the same site and on more than one occasion using a consistent assessment regime. Simply comparing the results of separate studies which observed tree health at different locations at different times is not a robust assessment of the decline in tree health. Unfortunately, this has been the pattern of scientific evaluation of tree health over many years. The first tree health survey in the MDB was in the 1980s. It was based on rapid surveys that consistently reported declining tree health. There have been only two studies for the Murray River where the health of river red gums had been assessed at the same sites at different times. They both reported a decline during the middle of the millennium drought, which is hardly surprising but not proof of any long-term trend in tree health decline.

River red gums, like most eucalypts, will shed and regrow their crown depending on environmental variables. For red gums, water availability is critical, and this is what it is adapted to do. It highlights the poor survey design by ecologists doing the tree health assessments. It seems obvious they lack the practical on-ground experience to differentiate between the stress periods, and even if they do have that knowledge, they are not incorporating it into their assessments. How do they know the difference between crown branches dying of old age or drought? During drought periods, it is common to see affected trees develop a dull lustreless foliage. Many trees that are entirely bare of leaves are declared dead when they are not. The problem is exacerbated when ecologists rely on satellite imagery for their assessments without ground-truthing and validation. Trees with a poor crown put out many epicormic shoots as they recover from droughts. According to CSIRO ecologist Matthew Colloff:

“Whether or not a tree has begun to recover from drought after several months of flood is a more accurate assessment of its viability than whether it looks dead after several years of drought. One robust indicator that trees are truly dead is where cracks in the bark have extended through the water-conducting phloem tissue, disrupting water uptake.”[18]

During the millennium drought, politicians again focussed attention on the MDB, and short-term politics reigned supreme. I believe Malcolm Turnbull’s main political legacy is the Water Act 2007, drawn up in the dying days of the Howard government. It is arguably the worst piece of legislation in Australia’s history. Turnbull wanted to return water to the river system come hell or high water. The act was developed in a very short time frame with little to no consultation with Australia’s water professionals or innovative farmers. The act established another bureaucracy, the Office of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder, to manage water recovery for the environment. However, it was doomed from the start because the Constitution gave the states legislative powers over water management, not the Commonwealth. As Turnbull argued:

“In the 1890s our founding fathers missed a big opportunity when they drafted our Constitution in not putting the management of interstate waters under federal jurisdiction. In 2007 we rectified that mistake with the Water Act.”[19]

Except he didn’t rectify anything. While Turnbull sought agreement from the States to cede their power to the Commonwealth, Victoria refused. The Constitution couldn’t simply be amended over a weekend to fit Turnbull’s political ambitions before an election. Turnbull failed to admit that an environmental lawyer suggested the Federal government could use its obligations under the Ramsar Convention to protect wetlands as the basis to regulate water use in the MDB. It meant that the Water Act 2007 was purely an environmental stick to take powers away from the states. From a social and economic perspective, the concerns and effects on the MDB constituents were ignored entirely.[20]

A new Labor federal government came to power in 2007 under Kevin Rudd. They believed they could save the MDB from ‘climate change’ and introduced the Water Amendment Bill 2008. The main instrument to achieve their policy ambitions was to replace the Murray Darling Commission with the Basin Authority (MDBA) because the MDBC had no control over the states, even though the MDBA was still subject to state politics. What was worse, Labor believed the environmental groups and the Wentworth Group about the dying river red gums. Once again, the mainstream media got interested and ran doom and gloom stories about the dying river system. Water allocations everywhere were cut.

Meanwhile, flooding rains arrived not long afterwards in late 2010. Nearly three-quarters of Queensland alone was underwater in a devastating state-wide flood. The MDBA was due to release its new plan using the ‘best available science’ and develop a sustainable diversion limit – the amount of water that could be extracted each year. However, it was politically fraught as it meant that water allocations would be cut.

Water buybacks and allocation cutbacks

Water Minister Penny Wong[21] decided to pre-empt the MDBA report and squander billions of tax-payers funds through Australia’s largest ever ‘environmental’ program dubbed ‘Penny’s from heaven’. She started a water buyback program buying water rights and large irrigated properties. Irrigators were pawns in a high-stakes political game.

Some farmers were desperate because of the effects of the prolonged drought and badly in debt. Wong took advantage of this. She used $10 billion, set aside by the Howard government, which included $3.1 billion to buy back over-allocated entitlements. Wong wanted a big deal to reinforce Labor’s commitment to constituents in the inner cities who favoured the environment over resource utilisation. She found it in the Kahlbetzer family, who were willing sellers. For $303 million, the taxpayer and the environment were supposed to be winners. But it was soon revealed that the government paid at least $40 million too much for the Kahlbetzer water licences. There will only ever be one Penny Wong for the billionaire Kahlbetzer family to borrow a Kerry Packer saying.

Before the government began its buyback, water prices were trading at $850 a megalitre. After the government splashed money around like confetti, the price rose to $1,250 a megalitre. The Kahlbetzer’s sold their water for $1,309 a megalitre. The main driver was different government programs competing against each other such as ‘Riverbank’, ‘Water for Rivers’, ‘The Living Murray Initiative’ and the federal government’s water buyback scheme. Bureaucrats had to spend the money regardless of any strategic imperatives and were ignorant of the progress of the other projects. They ended up competing with each other, significantly increasing the price of water. Struggling farmers saw this farce immediately inflate the debt-to-equity ratio of their properties, causing some problems with the banks. It was clear from the outset that Federal Labor placed the environment above any food security in the MDB.

Worse was to come. A guide to the upcoming MDBA Plan (Basin Plan) was released while flooding rains enveloped eastern Australia. It suggested water allocation cuts to irrigators of 27-37 per cent. The MDBA claimed it was based on “best peer-reviewed science” and was open and transparent. However, it was a rushed document and didn’t have enough information on the northern basin.

Furthermore, the guide relied on science that had nothing to do with the MDB as it erroneously claimed that the extra 3,000 to 4,000 gigalitres to the environment would “ensure the mouth of the Murray River would remain open most of the time”. However, it was patently clear the real aim of the Basin Plan was to artificially maintain the salty estuarine lower lake system of Lakes Alexandrina and Albert in South Australia as freshwater systems and discharge additional flows through the barrages in a vain attempt to keep the opening from the Coorong to the sea clear of silt. This equated to squandering the equivalent of Hume Dam’s capacity of three million megalitres each year.

The guide was released late on a Friday afternoon because of the predicted political fallout. The late Professor John Briscoe, a distinguished international water expert, was highly critical of the MDBA. He argued that the Basin Plan was developed through a “highly secretive we will run the numbers and the science behind closed doors then tell you the truth” process. He despaired that the MDBA chose excessive confidentiality and ignored “the immense world-leading knowledge of water management that had developed in Australia during the last 20 years”, which diminished Australia’s standing as a world leader in arid zone water management.[22]

By this time, the minority federal Labor government relied on the support of two independents. One of those, Tony Windsor, was the Chair of a Standing Committee on Regional Australia. Windsor and the Committee were appalled at the guide for the Basin Plan. They recommended a stop to non-strategic water buybacks and more investment in community-driven water efficiency projects. New Water Minister, Tony Burke, was forced to consider the economic and social factors from the political fallout. As a result, the government distanced itself from the guide and its recommendations for environmental flows. Instead, they commissioned a belated cost-benefit analysis. That didn’t mean, however, walking away from environmental flows as negotiations continued. The die had been cast, and any reduction in setting environmental water flows was widely seen as a poor political outcome.

In 2012, Labor legislated the Basin Plan dropping the environmental flow target to 2,750 gigalitres. After the Liberals returned to power federally, the dying Labor government in South Australia set up its own Royal Commission to look at the Basin Plan. Predictably, the Commission was scathing on everyone involved in the plan. Bert Walker QC expressed “admiring praise for the Water Act 2007, for its setting into legislation an environmental aim, informed by science”. However, he felt comfortable that politicians used their powers to draft legislation to try and circumvent the Australian Constitution. The whole management of the MDB had now descended into a political morass that served no one’s interests, including the environment.

If there is not enough water flowing in the system, it is not the fault of irrigators extracting too much water. Different regions face different problems due to a combination of factors. For example, the Murrumbidgee has a lot of tree plantations at the top of its catchment. The Riverina has drainage schemes developed to ‘artificially dehydrate’ the landscape to prevent the rise of groundwater because of salinity concerns in the past. And the Macquarie Marshes water has been directed away from key nature reserves by levy banks.

There is an alternative solution to providing more water flow in the MDB that current bureaucrats and scientists ignore or don’t know. More than 14 million hectares of vigorous regrowth occurs in the New South Wales section of the MDB alone, with many more millions of hectares of thickened woodland in both public and private tenure. Suppose these areas were thinned to bring the vegetation back to the pre-settlement levels observed by Oxley and Sturt all those years ago. In that case, catchment yields would deliver the additional megalitres for the environment at a much lower cost and help protect the existing food bowl.

The fallout

The tragedy of mismanaging the MDB is seen in the Riverland towns and cities that depend on the irrigators. Conglomerate agri-business companies loaded with capital purchased the water rights from the landholders and have established massive almond and citrus ventures. They have taken advantage of the billions of dollars on offer in an unregulated water trading scheme. Water trading is not new. There were informal arrangements between neighbouring farmers where one farmer traded excess water to the other. Today, everyone is involved in water trading in the MDB. State and federal governments, bankers, speculators, and full-time traders all have had a go.

Following concerns about the water buy-back scheme, the federal government directed the ACCC to inquire into the MDB water markets in 2019. They released their final report in March 2021. The ACCC found there were very few rules governing the conduct of market participants. There were trading behaviours that undermined the integrity of markets, such as market manipulation and insider trading. The most damning finding has been the lack of transparency within the water markets, with no one overseeing water trading activities. Irrigation corporations, set up by governments, are private companies that operate water service infrastructure to deliver water to irrigators. Still, in New South Wales, there are no requirements for them to register water trading activities. I have even read a claim that criminals could be laundering money within irrigation schemes because they don’t have to reveal their ABN on water transactions, most of which are over one million dollars.

Perhaps the ACCC should have inquired into the conduct of the Commonwealth and New South Wales governments, for one example of incompetence should not go unnoticed. Near Bourke on the confluence of the Darling and Warrego Rivers, the 96,000-hectare Toorale station was purchased in 2008 by the federal government for $24 million, supposedly to save the Darling River and convert it to a national park. Overnight, the Shire of Bourke lost 10 per cent of its business activity and 4 per cent of its rates. Penny Wong claimed the deal meant “an average return of 20 gigalitres to the Darling River each year” at the time of purchase. However, nothing has happened on the property despite drawing up a decommissioning plan to remove infrastructure to allow water to go to the Darling River. Consultants estimated the cost of decommissioning at a staggering $79 million. There are many environmental obstacles to removing the dams and channels because a ‘new ecology’ had grown in the 150 years since the station was established. After heavy rains and flooding in 2010-11, water spread out on the Lower Warrego flood plain, as it had done since the 1880s. Locals, especially downstream of Louth, watched aghast as the promised gigalitres of water failed to materialise in the Darling River. The Louth gauge measured a return of 7.6 million litres to the river system, representing just 0.01 per cent of the total water flow through the Darling River. Instead, millions of dollars of lost productivity from a productive farm have been lost with zero environmental gain. We now have a dysfunctional, third rate national park, all at taxpayers expense.

Penny Wong, Tony Bourke, and the MDBA bureaucrats still have their jobs and a livelihood. Some irrigators have nothing or are on the brink of bankruptcy. The purchase of the historic Toorale property is an excellent example of the futility of wasting millions of dollars to achieve little environmental benefit and cause damage to the local economy.

The Darling River isn’t a mighty river that continuously flows. Instead, it is artificially protected from dry periods via a regular flow fed by the off-river Menindee Lakes storage and the building of several dams on the tributaries of the Darling. During the recent droughts when the flow in the river nearly dried up, there were claims of corruption and water theft that compromised the environment and the whole river system. However, according to water consultant and writer Ron Pike, this most recent drought ‘crisis’ on the Darling River was exacerbated by the obsession of government and bureaucrats with environmental flows.

The policy of maximising environmental flows to keep the lakes at the mouth of the Murray River topped up and ‘flushed’ has caused a new wave of artificial floods that create massive environmental damage. When the construction of locks and weirs regulated the Murray River flow, and summer flows were increased to meet irrigation demands downstream, water engineers knew they couldn’t release more water than the river channel could carry – a quantity primarily dictated by the capacity of the Barmah choke and the Edward River off-take. Today’s bureaucrats at the newly formed Office of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder and the MDBA don’t seem to have this knowledge. They are overseeing the severe erosion of over 300 kilometres of the Murray River’s natural constraints. Trees and important riverbank habitats are being removed, resulting in erosion much more rapidly at various locations, including the Barmah choke.

The Murray River Council has had to consider engineering works to protect infrastructure on the river near Mildura. However, they face significant bureaucratic hurdles, with no less than seven government departments approving any works. It is also incongruous that the agencies responsible for this mess, the MDBA and the Office of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder, have no accountability to funding any restoration and repair work.

Questions are being raised about whether squeezing the water through the Barmah choke is really about environmental flows or more about hiding the massive transfer of water allocations from higher in the catchment to downstream users. For instance, 70 per cent of water rights from the Goulburn-Murray area have been transferred to the Sunraysia region since July 2003 to feed the Managed Investment Scheme almond farms. Thus the high current flows are an unintended consequence of getting massive amounts of water allocations to the almond farms.

The environment in the Murray-Darling River system is not being saved. Since introducing environmental flows, the Menindee Lakes were twice drained, and Broken Hill ran out of water. Put simply, the environment has a lot less to worry about from irrigators than it does from politicians, bureaucrats, green groups and academics.

The twelve months to June 2019 was one of the worst drought years in recent history. Many farmers went broke. They couldn’t afford the water. Others sold up to non-farmers who were cashing in on the lucrative water trading market. By spring that year, the rains arrived. The Murray River, below Yarrawonga, which is the start of the irrigation district, ran at minor flood levels – 15,000 megalitres a day for three months. Most New South Wales irrigators and farmers had zero water allocation during this period. They watched the water go past their properties.

The obsession with environmental flows has led to potential corruption of water trading, put irrigators out of business, jeopardised MDB food bowl enterprises, and has done nothing to improve the environment. The Office of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder and the MDBA have gleefully utilised the existing infrastructure they demonise to capture, store and regulate the release of environmental flows, but fail to acknowledge that without the storage dams and locks, the MDB system would experience low flows and drier periods much more quickly and for more extended periods causing much more pronounced difficulties in drought periods.

Impacts on the largest concentration of river red gum forests in Australia

Away from the large, isolated river red gum trees along the Murray River, the misguided environmental flows have impacted the Barmah-Millewa river red gum forests. It has been compounded by recent changes in land tenure and mismanagement.

Australia’s largest concentration of river red gum forests is located on the most extensive floodplain areas within the MDB between Tocumwal, Deniliquin and Echuca, covering over 70,000 hectares. Through this forest runs the Barmah Choke, the narrowest stretch of the Murray River. The flow of the river at the choke is restricted by the geological ‘Cadell fault’, which naturally causes the overflow of water into the Barmah-Millewa forests when the river flow is high. The choke has historically resulted in the river overflow spreading out into the forests via a system of natural effluents and runners, those on the east and south returning to the river in a relatively short distance. Those on the north and west feeding into the Edward River off-take, to rejoin the Murray several hundred kilometres to the west.

However, there is a common misconception that these river red gum forests existed at European settlement. On the contrary, they are an artefact of European settlement. Before the arrival of Europeans, the forests included black box (Eucalyptus longiflorens) trees and Aborigines used to keep the forest open with regular burns. In the early days, a horse and cart could travel through the forest unimpeded. The Europeans removed fire and replaced it with cattle grazing, which influenced ground cover and understory vegetation.

Historically, the red gum forests would flood naturally in winter and spring most years. However, since the regulation of river flows, the winter and spring floods were reduced, with more low-level flooding occurring in summer and autumn. The effects of river regulation were long foreseen and warned about by foresters in 1913 when water regulation was first being mooted on the Murray. The problems started to become evident after the completion of the Hume Reservoir in 1933. They were accentuated by the enlargement of the reservoir in the 1950s and the subsequent construction of the Dartmouth Dam.

The higher level of summer river flow has increased the area of permanent swamps or lakes connected to the Murray or Edward Rivers by low off-take creeks, except where they have been blocked or regulated. In the process, some of the higher quality stands of river red gum have drowned and been lost. There was a reversal of the previous pattern of lakes becoming swamps and of swamps gradually invaded by forest. For most of the European settlement period, the forests have been under State forest management in both New South Wales and Victoria. While foresters recognised these problems, they sought to develop management systems within the forests to cater for the new reality of regulated river flows and changed flooding patterns.

Left to their own devices, the river red gum forests quickly changed with the constant regulated summer overflow. The regulated flows led to the creation of thick, young stands of red gum saplings. Foresters dealt with this problem by introducing non-commercial thinning to reduce the stocking and improve the growth of selected trees. Early treatments were pretty conservative. In the 1950s, stands were thinned to about 420 trees per hectare. In New South Wales, a series of thinning plots was established in 1961, which showed an average stocking of over 3,000 stems per hectare. A thinning program, concentrated in the stands with tree diameters in the 20-30 centimetre range, retained co-dominant trees at approximately seven-metre spacings. During the 1960s until the late 1980s, the poisoning of saplings was widely used to improve the forest.

In an attempt to arrest the impact of water regulation on the Barmah-Millewah red gum forest, the MDBC developed a water management strategy to enhance the forest, fish and wildlife values. Between 1990 and 1993, reports were completed, and the Ministerial Council approved an allocation of 100 gigalitres of water per year to meet the needs of the forest ecosystem. In 1994, the Barmah-Millewa Forum was established to improve the ecological sustainability of the Barmah-Millewa forest and establish a framework to ‘better meet the flooding and drying requirements of the riparian forests and wetlands’.

However, these plans failed as calls were made to convert the state forests to national parks. The Victorian State Government requested an investigation by the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (VEAC) into the condition, management and use of riverine red gum forests on public land extending from Wodonga to the South Australian border in 2008. Predictably, VEAC recommended “the protection of the Barmah Forest as a national park”. As a result, the Victorian Government transferred 143,000 hectares of public land into national parks in June 2010. It included new river red gum national parks at Barmah and Gunbower forests. In July 2010, the New South Wales Government agreed to transfer nearly 107,000 hectares of the Millewa forest from State forest to the Murray Valley National Park and Regional Parks. There are now three large river red gum national parks divided by the Murray and Edward Rivers – the Barmah National Park, the Moira National Park, and the Murray Valley National Park. These parks are within 10 kilometres of each other, but today couldn’t be more different in appearance.

Parks Victoria made it clear they planned to “reverse environmental degradation and improve the management of Barmah National Park” when they assumed management control of the Victorian river red gum forest.

Below is a photo of the Barmah forest in November 2019. It has been flooded for so long nothing is growing in the forest. In 2018-19, unnatural floodwaters were forced upon the Barmah forest by the MDBA as part of the environmental flow obsession. The unprecedented flooding event, in depth and duration, led to reported high death rates of native animals. So much for Parks Victoria’s ability to reverse environmental degradation. Arguably, the combination of incompetent water and land management has created a worse forest since 2010.

The Moira forest covers an area of about 21,000 hectares in New South Wales. It supports a distinctive grassy wetland known locally as the Moira grass plains. In 2013, there were concerns of an alarming decrease in extent and cover of the Moira grass that dominated the treeless floodplain and served as a significant waterbird feeding ground. Unfortunately, it appears the Moira forest has been neglected since 2010. Today, it supports a vast number of saplings choking themselves out, leaving the forest looking like an alien landscape. It is a sad sight to see a beautiful forest on its knees.

A 400-hectare section of the Murray Valley National Park is in excellent condition. This is because the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service introduced a trial ecological thinning program to improve the declining health of river red gum forests. This trial was set up to gauge the effectiveness of ecological thinning to promote biodiversity in high stem density areas. It highlights that the extensive thinning programs carried out by foresters for nearly half a century within this forest were, in fact, an essential tool in keeping the forests healthy and an admission that converting the forests to national parks has led to a decline in the health of the forests. Through this continued active management and only flooding in wet years, this section of the Millewa forest is in a much better state of forest health than the Barmah and Moira forests.

The conservation agencies claim there is little evidence of significant change to the ecological character of the forests since the change of tenure, even though they acknowledge there is “some evidence that tree health has declined in the forests”. However, what is not in doubt is that the health of the forests has declined since 2010, except where thinning has continued. It seems clear that their boast that environmental degradation will be reversed under benign conservation management is patently unachievable. This is more so when water managers add to the wanton destruction by forcing excess water through the Barmah choke to meet political and environmental flow targets and the need to move large amounts of transferred water allocations from upstream catchments.

Summing up

As I stood on the banks of the Murray and Darling Rivers, immediately after the last drought, I didn’t see a dying river or any dying river red gum trees. Instead I saw a picture that differs from the constant squabbles about the MDB and its environment. Droughts are a common feature of the semi-arid climate. Droughts earlier last century regularly stopped the Murray River from flowing, with current flows only sustained by modern management and a network of water storages. If the Murray had natural flow during the more recent droughts this century, it would have stopped flowing, as it did in 1914, 1915 and 1923. Between 1885 and 1960, the Darling River stopped flowing at Menindee 48 times. In 1902-03, during the Federation drought, the Darling stopped flowing for 364 days! The mighty MDB has had to cope with everything mother nature has thrown at it, and it still acts like a flowing river supporting a range of environmental benefits.

What I did see, however, were signs of riverbank erosion that, at the time, I didn’t know were caused by environmental flows and transferred water allocations squeezed through natural narrow sections of the river.

I spoke to several farmers, residents, fishermen and regular holiday-makers while travelling on the Murray. They were in despair about the interference of city-based politicians, scientists and bureaucrats who have only succeeded in degrading the MDB with their environmental river flows and water buybacks. However, we all agreed if environmental flows for the Murray River have to be given a higher priority, it should be for reasons that benefit the environment, not those to suit fabricated myths about its opening, the maintenance of a freshwater system in an estuarine lake, nor the vilification of irrigators who have set up world-class agricultural systems, or farmers utilising water on floodplains in a closed system when the opportunity permits.

[1] Paul Watson, founder of Greenpeace

[2] These are some examples of the stories about the Murray-Darling River dying from a quick google search: ‘Is the River Murray dying?’ https://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/stories/s679708.htm; ‘The Darling will die: scientists say mass fish kill due to over-extraction and drought’ https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/feb/18/the-darling-will-die-scientists-say-mass-fish-kill-due-to-over-extraction-and-drought ; Save the Murray https://environmentvictoria.org.au/campaign/save-the-murray/

[3] Simons, M. (2020) Cry me a river: the tragedy of the Murray-Darling Basin. Quarterly Essay 77. Black Inc Books, Melbourne., Simons displays little knowledge of land and water management, relying on a certain narrative without considering more plausible alternative views. Her article displays a paternalistic and dim view of farmers and agriculture typically shown by most city-based people in Australia.

[4] https://mdbca.com/2018/05/02/pr-peter-gell-lake-alexandrina-estuarine-last-7000-years-construction-barrages/

[5] ‘The Darling will die: scientists say mass fish kill due to over-extraction and drought’ The Guardian, 18 February 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/feb/18/the-darling-will-die-scientists-say-mass-fish-kill-due-to-over-extraction-and-drought

[6] ‘Sundry Notes’ Western Herald, Wednesday 1 April 1903, page 2; ‘Wholesale death of river fish’ Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record, Friday 1 November 1929, page 12

[7] ‘What’s wrong with the Murray?’ Adelaide Observer, Saturday 9 November 1929, page 10

[8] ‘Dead fish in the Darling’ Barrier. Miner, Thursday 21 November 1929, page 3

[9] ‘Mystery river deaths’ Border Morning Mail, Tuesday 2 August 1938, page 8

[10] ‘River fish dying in thousands’ Ouyen Mail, Wednesday 20 August 1941, page 3

[11] ‘Darling River smells of dead fish’ Warialda Standard and Northern District’s Advertiser, Monday 5 February 1951, page 2

[12] See the Winter 2003 edition of Freshwater Fishing Australia; also annual Deniliquin Yamaha Fishing Classic in 2003 registered a record catch of 48 Murray cod.

[13] Marohasy, J. (2003) Myth and the Murray: measuring the real state of the river environment. IPA Backgrounder 15(5):1-28

[14]https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_Representatives_Committees?url=primind/waterinq/report.htm

[15] https://arr.news/2021/09/02/what-has-gone-wrong-with-water-management/

[16] The independence of this group has been questioned by a recent article in the Weekly Times. They highlight the close connections this group has with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Its Chairman is Robert Purves holds, or has held positions with prominent environmental groups including as President of WWF Australia. It was also reported that Purves purchased millions of Duxton Water shares, at the same time the Wentworth Group has been calling for more irrigator water buyouts “which would further shrink the consumptive pool and push up prices, benefiting Duxton [Water]” thus implying that he is profiteering in irrigation water trading. Deputy Chair of Southern Riverina Irrigators, Darcy Hare, described it as a national disgrace, saying that “games being played with the lives of farmers and rural communities for political and private gain need to be called out”. Mr Hare has called for a Royal Commission into water management and environmental degradation across the Murray-Darling Basin, “as it may be the only way to bring those at the centre of the mess to account”.

[17] ‘Green scum in the waters of the River Murray’ South Australian Register, Friday 13 April, 1888, page 6

[18] Colloff, M. J. (2014) Flooded forest and desert creek: ecology and history of the river red gum. CSIRO Publishing, Canberra

[19] Turnbull, M. (2010) The Water Act and the Basin Plan, December 9. http://www.malcolmturnbull.com.au/blogs/the-water-act-and-the-basin-plan/

[20] Turnbull claimed that the Water Act 2007 was a balanced act between the environment and human uses. However, the National Productivity Commission’s view of the act was that “it requires the Murray-Darling Basin Authority to determine environmental water needs based on scientific information, but precludes consideration of economic and social costs in deciding the extent to which these needs should be met”. The High-Level review of the MDB Plan in late 2010 stated that “the driving value of the Act is that a triple-bottom-line approach is replaced by one in which the environment becomes the overriding objective, with the social and economic spheres required to do the best they can with whatever is left once environmental needs are addressed”. See https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/murray-darling-water-recovery and https://mdbca.com/2016/08/23/professor-john-briscoe-the-water-act-of-2007-was-founded-on-a-political-deception/

[21] In 2008, Penny Wong attended a meeting with concerned citizens and irrigators, in Griffith, NSW. According to a source who was at the meeting and kept notes, when Wong addressed the large crowd, she immediately said words to the effect “I am not here to discuss with you your problems. I am here to tell you what I intend to do to save the Murray Darling Basin from climate change. Climate change demands that we do things differently and if that means that Australia has to import food, well that is better than allowing the rivers to die”. She then went on to tell the audience she had money to buy water and refused to answer questions.

[22] https://mdbca.com/2016/08/23/professor-john-briscoe-the-water-act-of-2007-was-founded-on-a-political-deception/

A fish kill in the main lagoon at Rockhampton in the late 1990’s was due to extremely low oxygen levels, caused by a fresh water inflow killing vegetation that had grown into the sides of the lagoon during drought conditions. The rotting of vegetation consumed the oxygen in a full lagoon, and the dying fish were mouthing the surface trying to get oxygen out of the air.

More generally, drought conditions will result in low water levels and poor water quality in stranded pools, hence the efforts of locals to transfer fish into larger pools. A natural process due to drought, not climate change. In the Fitzroy River, where only 14 percent of the total average flow is captured, a weir was being constructed near Marlborough, and the total flow of the river was being diverted through a 1.2 m pipe.

Well written and researched Robert. Very illuminating

Terrific article Robert. Sadly it reflects the incompetence of over-zealous technocrats acting on the whim of short sighted and ill-informed politicians. Australia is great in spite of itself ! Cheers, Bryan.

I did a double-take on footnote 17 (‘Green scum in the waters of the River Murray’). I thought it showed remarkable prescience for 1888. I need to take the red pill more regularly.